You cannot do everything. Neither can I, none of us can. A few weeks ago I attended both the Science Online and American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) conferences. An issue that kept coming up in discussion is how to be better at science outreach and communication. For scientists and communicators (and the many people who are both) it was clear to see that everyone wanted to be better. But, I noticed people getting frustrated, and sometimes even a little heated when it came down to the nitty gritty of HOW to be better.

No one person or group is, or can be, solely responsible for science communication. Science communication is an ecosystem that includes journalists, writers, bloggers, comedians, cartoonists, artists, video and audio producers, storytellers, social media enthusiasts, and scientists. What unites us is our end goal, we all want to share a love for science that explains, while also exciting people about science. How we go about achieving that end goal is different for all of us – and it needs to be. I would argue that the reason the science communication ecosystem has evolved to include so many different types of communicators is because we have a need for different voices communicating about science in different ways. The more quality communication out there, the better.

That doesn’t mean any one person can be a regular sci comm superhero and do it all. I can’t be a journalist, writer, blogger, artist, comedian, cartoonist, video and audio rockstar, etc. I don’t know about you, but I don’t have time for that. I don’t know anyone who does, and communication is my main focus. I think it’s a little bit crazy to expect scientists to be scientists and also communicators, but on top of that layer on every type of communication. You alone can’t reach everyone, that is why we need all of us out there communicating in different ways. It is the only way we can reasonably expect to reach a wide audience.

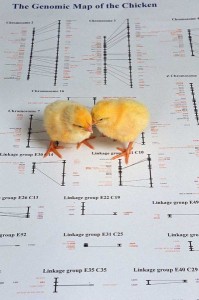

I’ve seen a lot of conversation lately about the idea of scientists writing lay friendly abstracts for their scientific papers. I’ll be the first to admit lay abstracts are helpful. I recently sat with a researcher who made a graphical abstract to represent the research in pictures, it was awesome. But, I’ve seen the lay abstract idea get pushed even further into scientists writing full articles for the public. Where do we draw the line? If all the scientists get out there and start writing lay-friendly whole articles for publication in the mainstream…well then what the heck am I supposed to do all day? This isn’t about jargon (please, please, let’s not have the jargon fight again) I certainly don’t think that all scientists are bad at communicating. Some are very good at it, and some aren’t so great. But you know, I would be a lousy scientist. I’m not trained to be a scientist, those aren’t the skills that I have. What I am trained to be, is a writer.

Writing well is something that requires certain skills and know how, in addition to a little bit of talent. It is something that develops over time, the more you write, often the better you’ll get at it. All of the other modes of communication, audio, video, etc. include their own skill set. Sometimes I feel like people take for granted that everyone should be able to write and communicate well. There is a distinct lack of appreciation for the level of skill and dedication it can take to communicate well. That’s not to say people can’t learn how (or that for some, it will come much easier than it does for others) – but the same way I can’t just snap my fingers and be a great scientist, I don’t think you can just wish to be a good communicator and make it so. It takes time, which is the one thing that is in short supply for all of us.

I don’t want or expect scientists to do my job for me. I want to write, I just need the help of scientists so that I can. One thing, in my opinion the most important thing, that scientists can do to be more involved in outreach is to make themselves available to science communicators so we can ask our questions and then synthesize the material for a public audience. It takes time to sit with a writer, I know, but it is time well spent. It is also time that doesn’t require developing an entirely new skill set.

If scientists have the time to learn how to communicate well and then get out there and do it, that’s great. Direct from the scientist themselves communication is awesome. I value it highly. But I also don’t think it’s fair to expect scientists to do their job and then also do my job. Not when being a scientist is itself basically two jobs because in addition to being a scientist, most are also professors and teaching itself is it’s own career. I’m all for stepping down from “the ivory tower” but that doesn’t have to mean becoming a master communicator yourself. Outreach, like communication, comes in many shades.

If you don’t think you have the skills to write well, and you think your time could be better spent elsewhere, then fine. If you’d rather give a talk for an audience or demographic that you normally wouldn’t reach because that’s what you feel comfortable doing, then do it. If you’d rather sit with a journalist for an hour and just talk about your research so that they can go get the article in the media, then great. If the best way you think you can reach the public is by joining twitter and then adding value to conversations about your field of expertise, then do that. If you want to sit in front of your computer and film a short video of you summarizing your work, do it. I’m all for doing something, but that doesn’t mean you have to do everything.

I’ve said before in blog posts about learning to code, that I don’t think journalists should be required to excel at every different type of communication. Try, sure. Try out new things. Try new ways of communicating and reaching people. Be open. But there is a difference between trying new things to see if you enjoy or are good at them, and a blanket expectation that you have to use every single means of communicating out there. Similarly, I don’t think you can expect scientists to do every different type of outreach. Some outreach, sure. Scientists can be open to new things too, and try them out to see how they fit. But just like I don’t enjoy code, some scientists might not like Twitter. It’s okay to not like Twitter. I choose to communicate in ways that I am good at and enjoy. I love Twitter, that’s why I use it. I don’t see why scientists shouldn’t have the same rule of thumb when it comes to outreach. There are so many different ways to get a message to someone. We need all of the ways, and we need different people to try them.

I’m not a sci comm superhero. I don’t do it all. Mostly because I like to sleep, and I like my sanity but also because I’m not very good at certain things. I can’t draw to save my life. You’re never going to catch me trying to be a sci scribe. I’m okay with that, because drawing isn’t how I communicate. It’s not what I do, and it doesn’t have to be. Scientists don’t all have to be writers. There are other ways to get your message across without having to be a sci comm superhero. I’m not saying don’t try, but let’s just be realistic here. Yes, scientists need to communicate about their work, but I’m not going to expect scientists to communicate in every way when I don’t even do it myself.

You don’t have to do it all just to do something. Even if that something is just talking to someone who does want to write, that itself is a positive step. So maybe, rather than trying to do all the things all the time by ourselves, we could just try to do a few things, and rely on each other to fill in the gaps. That way we as the science communication ecosystem can reach the most people in the best ways. Is that too idealistic? Maybe. But I can hope can’t I?