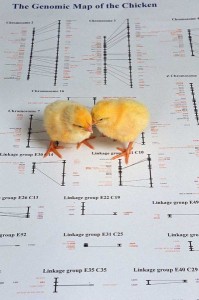

I am a baby chicken. Not literally of course, but figuratively speaking I am a little chick of a science writer. Fledgling, if you will. Continuing with this analogy, I recently left my incubator in the journalism school at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and am now out in the world looking for work as a journalist. It is tough out here for a baby chicken, and any clips and exposure you can get have tremendous value. This is why I think it is downright wonderful that Scientific American has a blog in their network dedicated to new and young science writers.

Borrowing from the blog’s about description, the

SA Incubator is, “a place where we explore and highlight the work of new and young science writers and journalists, especially those who are current or recent students in specialized science, health, and environmental reporting programs in schools of journalism.”

USAGOV-USDA-ARS via Wikimedia Commons

On the SA Incubator you can find profiles of new and young science writers, links to interesting work from these science writers (and others) chosen by the blog’s editors, profiles of student run science publications, and other assorted posts on topics of interest to writers who are just getting started.

I think you would be hard pressed to find a science writer who doesn’t aspire to see their name in

Scientific American. Speaking from personal experience, having

a profile dedicated to you and your work on a

Scientific American blog is a thrill. It was an experience that I enjoyed so much that I wanted to learn more about why a publication like

Scientific American would set aside such a great space on their network for someone like me. What is in it for them?

To answer that question, I turned to the Blogfather himself,

Bora Zivkovic. The SA Incubator is written by Zivkovic, who is the Blogs Editor at

Scientific American, and Khalil Cassimally, community manager of

Nature Education’s Scitable blog network.

How Big Can It Be?According to Zivkovic, there are a lot of reasons why the

Scientific American network includes a blog about new and young science writers. One reason is the network’s size. When it launched in the summer of 2011, I remember being struck by the sheer volume of awesome that is included in

Scientific American’s blog network. While it is a large network, there are still limits on how many blogs can be included. The cost, time and effort it takes to manage the network are obvious reasons why there would be a limit, but Zivkovic also pointed out that some of the value of having a network in the first place comes from it being of a limited size.

One of the coolest things about the Scientific American network is the diversity of writers and topics. If the network got any bigger, it would be difficult for the average person to read all of the posts. If the number of posts becomes daunting, the reader’s habits will change from browsing to more targeted reading. “Instead of at least occasionally checking out all of the bloggers they only focus on their favorites (some readers always will, but at least some don’t) – thus the ‘network effect’ for bloggers is diminished,” said Zivkovic.

What does that mean for the SA Incubator? There simply isn’t space for everyone to have their own blog on the network. Therefore, creating a blog that includes a lot of work by a lot of people is a way to increase the number of voices in the network without it becoming completely overwhelming. It also gives Scientific American a chance to bring new members into the family of bloggers without diluting the existing community too much. According to Zivkovic, this helps maintain a balance between keeping the network fresh and diverse while still keeping it coherent and friendly. For the new and young science writers it is difficult to compete with more seasoned bloggers for a space in the regular network. The SA Incubator gives new and young writers a space where they can participate and be seen and heard without taxing the network.

For new and young science writers, the SA Incubator is also a way to have a presence in the network without having to take on the full responsibility of having your own blog. Zivkovic explained the juggling act new and young writers perform: “Many of the youngest writers are still in school, too busy with class assignments, or are in internships, or are too busy breaking into freelancing to be able to blog with regular frequency.” The SA Incubator gives these writers the opportunity to get noticed without adding to the stress and demands of finding your way as a journalist.

Getting Over The Wall, and Getting A Job

Another reason to include a blog for new and young science writers is because the job we do is so important, but so competitive and difficult to break into. There is a big difference between a general reporter and a science writer; the more skilled science writers we have out there, the better. When I think of science writers I admire and the good work that they do; good to me meaning factual, nuanced, interesting and true; I’m inspired and intimidated. Inspired because I really believe science writers can make a huge difference in helping people understand and appreciate science, and intimidated because the bar has been set very high. The more people we have out there combating the bad science coverage by debunking, clarifying, and explaining, the better.

When journalists talk about this we tend to refer to it as the

Push vs. Pull strategy. Essentially, it is the idea that if the general public isn’t drawn to science stories on their own (pull) perhaps we can bring the science stories to them wherever they are (push). To be able to be able to pull people into places where they can access science content and also push out science content everywhere we can, we need a large well trained work force. Increasing the profile of new and young science writers and helping them get the opportunity to do this job is the value of the SA Incubator.

According to Zivkovic, helping get new and young science writers hired is part of the joy of running a blog like the SA Incubator. If you are looking to hire a science writer, you can find them at

Scientific American on the

blogs homepage, in

the weekly linkfests, in the

ScienceOnline interviews, on the

Guest Blog and on the

Incubator. As Zivkovic said, “Hire away! Let the good young writers infiltrate the media giants and transform them from within.”

For Zivkovic, giving new and young science writers a hand really is about community. To understand why, he recommended

reading and

watching Robert Krulwich’s commencement speech to the Berkeley Journalism School’s Class of 2011, which I too recommend. Krulwich talks about how to get over the wall that new writers face. The wall is what separates you from the journalists who actually get to do what you want to do.

Zivkovic isn’t a trained writer, but he started blogging about science back in 2004 anyway. He was invited to a blogging network in 2006. His job as Blogs Editor at Scientific American? Yeah, safe to say his blogging had something to do with that. This success story is something he attributes to the science blogging community. Blogging is what got Zivkovic over the wall, and now he is running the SA Incubator to help people like me figure out a way to pull themselves up over that same wall.

“These people became my community, my second family. It is that community that helped me every step of the way. They cheered me on. They hit my PayPal button when I was jobless. They pushed for me to get hired. They keep coming to ScienceOnline, they hug me at tweetups, they submit posts to Open Laboratory, they say Yes when I invite them to join the SciAm blog network, they were there for me all along and helped me climb over the wall. It’s payback time. It is now my turn to help others climb that wall, too.”

That is why he gets to be the Blogfather.

We’re In This TogetherAs if that isn’t enough, Zivkovic mentioned one other reason why he thinks the SA Incubator has value for the

Scientific American blogs network, the concept of horizontal loyalty. Horizontal loyalty is a phrase borrowed from the Krulwich talk I mentioned earlier (seriously,

go read it…after you finish this.) It is making something of yourself alongside people who are also trying to make something of themselves. Do it together. Make something. Be something. For Zivkovic, this is very much a part of why the SA Incubator exists.

“It is not so much about helping new writers get jobs in old media companies (though that helps pay bills for a little while). It is about helping them find each other, build relationships, build friendships, build start-ups, build a whole new science writing ecosystem that will automatically do both

‘push’ and ‘pull’ and reach everyone and displace bad science reporting from the most visible areas of the media, while providing them with a living,” says Zivkovic. “This requires a lot of them, but they need to know each other and work together toward that goal.”

So there you have it. The SA Incubator: Helping Hatch Science Writers Since July 2011. Creating a community for those of us who so badly want to be out there working alongside the more established writers to tell what I think are some of the most important stories there are. I was truly humbled to be counted among so many great science writers and be given a space on the SA Incubator. I wrote this post because I’m grateful for the chance to be included, but also because I really believe having a space for new and young science writers to connect and promote themselves is important. Baby chickens (and baby science writers too) all have to start somewhere.

Now, if you are a fellow fledgling science writer I know what you are thinking. You are thinking how can I get in on this? You can start by following, subscribing, etc. on

Twitter,

Facebook, or

Google+. You can start commenting on the blogs in the

Scientific American network (Zivkovic reads all the comments.) You can also go the direct route and just introduce yourself. Send an email, pitch to the Guest Blog, or send Zivkovic a link to some of your work. A direct message on Twitter would work too; you can find him

@BoraZ.