The more I learn about and bear witness to the world, the more I’ve realized that my classroom education left out some aspects of history that give context to world and national events, and shape how I understand and interpret them. Reading is one of the best ways I’ve found to introduce missing perspectives and fill in gaps in my education.

Growing up I certainly had an awareness about the civil rights era–we learned about Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X in school. But, even though I learned about these important people, there are so many others whose names I should also know, that I don’t. Pauli Murray and Katherine Johnson are just two of those names. Luckily, reading brought their stories into my world, and helped add depth to my knowledge about the various contributions of people of color to the United States during the civil rights era.

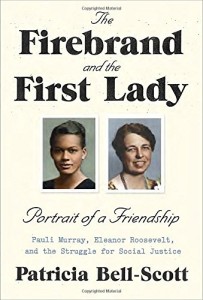

The Firebrand and The First Lady by Patricia Bell Scott

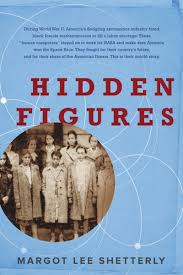

I learned about these two women by reading books that I think offered a lot of good information about US history and the role that women of color played in it: The Firebrand and the First Lady by Patricia Bell-Scott and Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly. Science writing and science history tend to comprise more of my reading list so Hidden Figures was in my conventional wheelhouse more so than the Firebrand and the First Lady, but both books were still quite different choices for me, being written by and about women of color. While I’m embarrassed by how little of my bookshelf came from or is about women and people of color, it is something that I can and am consciously fixing.

The Firebrand and the First Lady tells the story of the friendship between Pauli Murray and Eleanor Roosevelt. Murray was a lawyer, a civil rights and women’s rights activist, and the first black women to be ordained as an episcopal priest. Eleanor Roosevelt was the first lady of the United States from 1933-1945, US representative to the United Nations 1946-1953, and an important political figures in the women’s rights and civil rights movements. With neither woman alive to speak for themselves, the author draws heavily on the letters they wrote to each other.

Being able to see the letters they wrote to each other, especially when they disagreed, was amazing. It really was a snapshot from another time, where people with opposing views could find common ground and unite around a shared respect, treating each other with civility and thoughtfulness. It just struck me as sweet and sad that there was once a time when a young woman could reach out to a political figure and not just get a reply, but get true buy-in and a relationship that lasted the rest of their lives. I don’t think we currently live in such times, although this lovely piece by Jeanne Marie Laskas about how President Obama handled his mail, reading 10 letters a day from the public was a nice reminder about how important it is to have elected officials who hear you.

In telling the story of Murray and Roosevelt’s extraordinary friendship, the author gave an overview of the civil rights movement and the role that women played in it. But it was also an extremely American story, about how regular people built themselves up through education and hard work to leave an imprint on the world through the changes in policy and law that they helped bring about. The book left me not only knowing Murray’s name, but also with a profound respect for her.

I felt sympathy for Roosevelt, being a power broker but with limitations, and needing to figure out what she could do, what she should do, and how to pick which battles were the ones worth seeing through. She wasn’t able to do all that she wanted to, and yet she did so much more than most. But I was glad to see that Murray always held Roosevelt’s feet to the fire. In some ways, seeing Roosevelt’s responses felt like a master class in how to deal with criticism, and how there is always more that we can all do to help improve life for those around us. Being pushed to be better is a gift in many ways, but it’s also an endorsement of your own worth– that you’re worth improving.

Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly.

Hidden Figures is quite a bit more well known, now that it has been made into a box office-topping film. Despite there being a movie version, the book is certainly worth your time. It tells the story of the black women “computers” (in the literal sense of “people who do computations,” but really mathematicians and engineers) who worked at NASA during its formation and at the dawn of the space race. It’s been written and said by others that the fact that this story hasn’t been told before is amazing. I certainly am not the first person to notice that this is a trend, the contributions of women of color being erased from the history that gets handed down. I’m glad that this book is as popular as it is because it is bringing this bit of history to the forefront and giving the amazing women whose story the book tells the place in history that they deserve.

One of the important things about Hidden Figures that has been said in this article and elsewhere is that, while it might be about events that took place from the 1940-1960s, there are still trends and themes from then that echo through research institutions today. Certainly for women of color working in physics today there are still numerous barriers to success and discrimination that white women and women in other fields don’t encounter.

Ultimately, I recommend both of these books, they are beautifully written and offer a point of view that I found incredibly valuable for expanding my understanding of the role that women of color played in US history. That context is important for understanding the tumultuous political climate of the world today, and I’m grateful to the authors for telling the stories of these women.