Part Three: Aftermath

Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I?

Calm down brain, you’re laying down. Do you remember down?

Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I?

Brain, we’ve talked about this.

Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I?

Brain, you’re going to have to figure this out. I know. It’s different.

Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I?

Down is still down, it’s always been down.

Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I? Where am I?

Suit yourself, I can’t make you.

Lying in a hospital bed with the lights off, my brain is screaming into a void. It doesn’t like the answer, or lack thereof, it is getting in return but it just keeps screaming. This is incessant vertigo. That is how it felt after surgeons cut into my brain to remove an acoustic neuroma. My brain was in a panic, trying to find its place in the world, but the input it typically relies on was damaged first by the tumor and then the surgery. There is no information streaming in from one of the usual sources, and my brain is having trouble coping with its loss.

Symptoms and lingering effects

Rehab to regain my balance, trying to stand on one foot and tap the other in front of me while standing on a piece of foam (treadmill isn’t on). Photo by John Podolak.

Of the 12 cranial nerves, the eighth controls and senses both sound and spatial orientation. An acoustic neuroma is a tumor that grows on this acoustic/vestibular nerve. Mine grew on the right, and so my hearing and vestibular system have both been damaged beyond repair on that side. The vestibular system is a part of your inner ear, and it works in concert with your eyes to sense your spatial orientation, giving you balance. It’s made up of two canals, and small crystals that move when you move and settle in response to gravity’s pull. Since vestibular function is closely linked to your vision, problems with this system are diagnosed by studying eye movements. Together your eyes and your vestibular system signal to your brain to figure out where you are in space.

Vertigo, which I’ve explained as living in a world that won’t stop spinning, is a common symptom of vestibular dysfunction. However, not all vestibular problems result in vertigo, and you can experience dizziness and balance problems that aren’t vertigo. I’ve struggled to find what I feel is an accurate way to describe what vertigo is like, and to differentiate it from other types of dizziness.

Prior to my surgery, I had a positive Dix-Hallpike test, which is used to diagnose vertigo. For this test you put on goggles that block out light and lean back with your head unsupported and turned all the way to the right or to the left. If you have vertigo, it will be triggered by this maneuver because, without input from your eyes, your brain struggles to orient itself.

Immediately following the surgery my vertigo was more intense that I’ve ever felt it, to the point that I was constantly nauseated. That is when I started describing it as a world that never stops spinning, or constantly riding Space Mountain. I had been told to expect this, so, unpleasant as it was, at least it wasn’t a surprise. The spinning lessened everyday after the tumor was removed, and, around the four-week mark post-surgery, the vertigo mercifully stopped. I recently had another Dix-Hallpike test and didn’t register a response, which is great.

I still have difficulty balancing, which is evident when I’m walking or going up and down stairs. If I try to walk with my eyes closed, it’s game over. Still, this is an improvement from the way things were in the hospital, when I couldn’t walk without assistance. I may wobble around like I’m hammered, but I can do it on my own. Vestibular rehab, which is a type of physical therapy, should help retrain my brain to balance. In some ways it feels like my brain is having an existential crisis, and, while I would like it to decide what it wants to do with itself, I know it takes time to adapt.

From physical to mental

Since the surgery was pushed earlier, it was only after the procedure that I started to process anything. Recovering from this procedure left me a lot of time to think, because I found it hard to focus on anything around me. Eyes closed, quiet, but awake, is a state I spent a lot of time in. Doing a lot of thinking, but not necessarily coming to terms with my feelings. People keep asking me if I’ve cried, or if I’ve gotten angry, but I’m not sure I’m sad or angry. I’ve had moments of course, and I get frustrated with myself when I struggle to do simple tasks, but I’m largely in good spirits. I feel lucky and loved more than anything else.

My worst moments come when I start getting down on myself for getting down. I’m impatient. I want to be back to normal. I want my life back. I want to be able to do things for myself. I want to walk without having to reach out and steady myself. I want to go back to work. I want my body back, because, in a lot of ways I feel like my body has been hijacked. Then I get annoyed with myself, because I’m going to get all of these things. I’m going to make a complete recovery, and it is only a matter of patience until I get there. I know I’m allowed to feel frustrated, but I try hard to maintain a realistic perspective about what has happened, and all the things that will happen because I’m still here.

That leaves things progressing incrementally. I’m anticipating being back on my feet sometime in June, and am looking forward to returning to the science communication world. I’m still doing a lot of thinking, and have a lot of emotional processing left to do, but I get a little bit closer to coming to terms with it everyday. As I’ve been reflecting, there are a few things that I’ve taken away from the whole experience which are not particularly earth-shattering, but are certainly foremost in my mind.

Things to take away

Before I left the hospital, with my sorority sisters. One of us isn’t looking their best. Photo by John Podolak.

First, as much as this happened to me, it happened to everyone who loves and cares about me. I’m so grateful to my friends and family for dropping everything to be at my side through all of this, and I think it is important to remember that this was traumatic for them. My parents keep talking about what I went through with the surgery, but I can’t imagine what they went through, watching the clock, waiting for news as an entire day slipped away, far longer than anyone predicted. I didn’t come out of the operating room until well after 10pm, and I know friends scattered across different cities were up watching their phones, waiting to hear how it went. I missed the majority of the drama either unconscious or blissfully unaware thanks to painkillers, so I think they had it worse. I’ve experienced such an outpouring of love and support, and have been so well taken care of – but caretakers need care too.

Second, never underestimate the power of an excellent nurse. I had two absolutely fantastic surgeons, and my primary care physician is awesome, but I also had terrific nurses. The nurses were always there, answering the majority of my questions (or helping me get the answers) for everything from tracking down my missing shoes to explaining what kind of medications I was taking and why. I know my Mom made a lot of late night phone calls to the hospital to check on me, and the nurses always fielded her inquiries in a calm and positive way. My nurses were all pretty awesome, and it made an unpleasant hospital stay that much more bearable.

Third, young and completely healthy isn’t protection against a medical emergency. You may be fine now, but life could have a curve ball headed your way, and you need insurance. I can’t even begin to imagine this experience without health insurance. I haven’t received the bill yet, but the costs associated with my care are going to be astronomical. Knowing I’m lucky enough to have primary and secondary insurance to help cover those costs has been such a relief.

Fourth, I have a new appreciation for what it is like to not be able to do something. I know I’ve said before that I can’t do something when really either I won’t, or just don’t want to do it. Having now experienced what it is like when you really can’t do simple things, I don’t think I’ll be mischaracterizing my abilities again. I also have a new appreciation for what a luxury it is to be able to sweat the small stuff. If your life is such that you can get worked up about things like traffic or a last minute meeting, you’re doing pretty darn well. There is so much that now seems like a waste of time or energy. It’s a trite truth that you don’t know what you have until you almost lose it, but I certainly have a renewed appreciation for all the good there is in my life.

The last thing I’ve been cogitating on (for now) is how important it is to trust yourself. I knew that something was wrong with me, long before I was actually diagnosed. I dismissed my symptoms for a long time, suffering through them rather than facing the reality that something serious could be wrong. Naturally, I’ve been blaming myself that things became as dire as they did, but I’m coming around to the idea that beating myself up about it isn’t exactly productive. This started out as dizziness and headaches, which could have been so many things besides an acoustic neuroma. It’s not surprising I and everyone I talked to about it brushed aside the idea of a tumor. It’s important to be your own advocate, and find a doctor that will listen to you. The first hearing test I took said I was fine, even though I knew I wasn’t. I’m so grateful to my primary care physician for listening to all of my symptoms and pursuing my case with a CT. She might not have been the one making the cuts, but I don’t think it’s a stretch to say she saved my ability to move my face by making sure I was diagnosed properly.

What I’m taking away most is that you can’t hide from your health, and if you try, it’s likely to come crashing through your life like a hammer. I’m just glad I’ve got a chance to pick up the pieces.

Part Two: Surgery

It’s too bright in here.

No. No, no, no, no, no. I don’t want this.

WHAT is that? They didn’t tell me about that.

I don’t want it, I don’t want it. I want to get up.

No. NO.

I’m going to be sick. I AM GOING TO BE SICK. Can’t you hear me?

I don’t have to calm down, this is wrong, I don’t want to be here.

No. No I don’t need this, I don’t want this.

Let me up. LET ME UP.

I’m going to be sick, again. AGAIN.

Morphine?

I don’t want to be here.

It’s too bright.

I’m told I didn’t wake up in the Post-Anesthesia Care Unit (PACU) with grace. I think perhaps luckily, I don’t remember the majority of the experience. What I remember most about waking up following 12 hours of brain surgery to remove an acoustic neuroma (more than 14 hours away from my family) is being angry that I was hooked to so many devices. I had three IV needles (though only one was in action), a catheter, a plastic bulb connected to an incision in my belly button collecting fluid, a heart monitor with five attachment points, and I couldn’t move my head because I had a heavy bandage wrapped around my brain like a donut. I woke up angry, and I woke up confused, and I woke up feeling, as I apparently slurred at my family, “aaawwfullllll.”

I was angry and confused. Either it was not explained to me, or I never processed the fact that I would have a catheter. Why this horrified me to the level that it did, I’m not sure. The sense of helplessness I guess. How suddenly and unexpectedly I had been transformed from an able-bodied 26-year-old, to unable to exert any control over even the most basic functions of my body made me confused. I wasn’t prepared to wake up in this new reality. I think, “will you put a catheter in me while I’m under anesthesia,” is something I should have asked when the doctors repeatedly beseeched me, “do you have any questions.” But, I didn’t think to ask. Even though it is obvious that I would need one, I hadn’t considered it. I hadn’t considered it because it didn’t even register as something to consider. I didn’t know that I didn’t know.

When I woke up connected to bags and tubes and needles late Thursday night I flipped out. My lack of grace included struggling to sit up, arguing that I didn’t need a catheter, and poking at the bulb collecting fluid, while repeatedly vomiting (into my oxygen mask at one point) before an increased cocktail of sedatives and painkillers finally took the fight out of me. At that point, though I don’t remember my Mom being there, she assures me I vomited on her too. Less than 48 hours before, I thought I would have surgery perhaps in a month. I thought I would go back to work for a while. I thought I had time to get ready for this.

Progressing too quickly

Only a week before I channeled Linda Blair from The Exorcist in the PACU, I was diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma. My diagnosis followed months of symptoms like headaches, dizziness, vertigo, hearing loss, ringing in my ear and numbness in my tongue. It was a long process to get an accurate diagnosis, and I had been assured that my type of tumor was slow growing. My doctors told me to take time to plan for my life to be disrupted by the surgery and recovery. These same doctors warned me to pay attention to the feeling in my face. The numbness I was experiencing in my tongue may just have been a starting point, so, if any other numbness occurred, my medical team needed to know. It could be a sign that the tumor was growing faster than anticipated, a sign that it wasn’t benign after all. If my doctors were going to save my ability to control and feel my face, it was important that there be as little preexisting nerve damage as possible. A week after being diagnosed, I woke up unable to feel half of my face. I was numb from cheek to chin on my right side. Not wanting to be alone, I did what made sense to me, and I went into the office.

I called the doctor too of course, and left a message with the patient coordinator about my new symptom. While I waited to hear from my phsicians, I worked. I tried to answer emails, and tie up some loose ends to square things away. My doctor asked me to come in to see her that afternoon, so in the spirit of “just in case,” I set my out of office message. A friend picked me up and drove me to my appointment. My doctor explained that she felt we needed to get the tumor out as soon as possible, that we really couldn’t wait because my symptoms were worsening at a worrying rate. “Tomorrow,” she said. Tomorrow? I should probably call my parents, huh?

I won’t even begin to speculate what this entire process has been like for my parents. I know calling my Dad to tell him that I needed brain surgery the next day was not easy, so I can’t imagine what it was like on the other end. Luckily, we had already decided what type of surgery I would have, and had been able to meet the surgeons. So, while my parents and my brother rushed from New Jersey to Boston, I was admitted to the hospital. My friend and I walked right from my doctor’s office into the emergency department and explained that I needed to be admitted. My boyfriend joined us, and the three of us switched from the emergency department to a room across the street by ambulance, then back across the street again by ambulance to a different room. I kept offering to walk, but rules are rules and I wasn’t allowed. Of course, I was rewarded for following the rules by losing my shoes during the room switching.

By now Wednesday afternoon had faded into Wednesday night. Things had moved so quickly I hadn’t had time to think about the reality of what was about to happen to me, to my brain, or to my life.

The Procedure

I left my friend and boyfriend sitting in my hospital room so I could get a pre-op MRI. I don’t have a problem with closed spaces, or noise, and I’d been fine during an MRI the week before to diagnose the tumor. So, when my nurse asked me if I needed anything to help me stay calm, I told her no. This was a mistake.

I didn’t really anticipate how LONG I needed to be in the MRI, because the one I’d had a week earlier lasted only 45 minutes. I also overestimated the strength of my emotional state. This time, the technicians needed to take pictures of the tumor to make sure it hadn’t grown. Then they also needed to image my entire spine to make sure there were no additional tumors. I was in the MRI for two hours. Alone. With my brain. My broken brain.

They tell you to hold as still as you can, but I sobbed for the entire last half hour. After the tumor was out, during a follow-up scan, one of the technicians told me that I was “a legend down here” for what had apparently been an out-of-the-ordinary, marathon, late night session.

Adding insult to injury, when I finished the MRI, the technicians placed garish glow-in-the-dark stickers, ringed in dark marker on my face. These stickers would serve as a map for the machines the next day, but that night I looked like someone stuck Lifesavers to my forehead.

When they wheeled me back to my room, I was still crying nonsensically and apologizing to absolutely everyone for losing my shit. This is how I entered into the first meeting between my family who had arrived from New Jersey and my new boyfriend, because, on top of brain surgery imploding any sense of normalcy in our lives, dating is still one of life’s most awkward rituals.

I eventually calmed down and tried to sleep, which anyone who has ever spent time in the hospital knows is not easy. It was morning and surgery time in the blink of an eye. They transferred me to the pre-op clinic, where both of my surgeons (one an ear, nose, and throat specialist and one a neuro specialist) came and talked to me. They ran through the procedure. They initialed the parts of my body they intended to cut. They explained the risks, all the things that could go wrong. I spoke to two anesthesiologists. I spoke to my nurse. I signed the consent forms. Everyone asked if I had questions – I did, I just didn’t know it, so I asked nothing. I gave my family a goodbye hug, and was wheeled away.

The last thing I remember is seeing one of my surgeons, and being asked questions – Who am I? Where am I? What day is it? Why am I there? Then there is nothing until I came to in the PACU, confused, upset, and angry.

I’ve been actively not thinking about the reality of the surgical procedure itself, because it is overwhelming to think that multiple people have literally seen my brain. My surgeons cut through the bone behind my right ear, and, because their approach cut a nerve completely, they destroyed my ability to hear on this side. This means I’m now deaf in my right ear. Part of the surgery involved packing the hole in my skull with fat taken from my belly button. This is what made the bulb at my abdomen to collect fluid necessary.

My Dad and I taking a hospital selfie. I was rocking the taped on glasses, him the mask and, yes, that is a cigar.

My family had been told it would be an all day surgery, but it took far longer than anticipated. One of the things the doctors had warned me might go wrong – “stickiness” of the tumor – did. The tumor was clinging to my brain, refusing to let go so easily. So my surgeons took extra time, ultimately clocking in at 12 hours after teasing out every piece. But they got it all, and were able to save my seventh nerve and thus my ability to control and feel my face. While there is no such thing as an ideal brain tumor surgery, my team got it all and avoided any damage to my facial nerves.

I think the decision to move quickly on the surgery was the right one, but it definitely didn’t give me time to process what was happening. I’m certain that contributed to my performance in the PACU. I woke up in a completely new reality that I wasn’t prepared to face. Toward the end of the day on Friday, my memories of the PACU become a little more solid. Apparently, I kicked off my hospital socks as part of my defiant outburst, and I remember being told I had the nicest feet there, which is amazingly awkward upon recollection. I remember my Mom and Dad being there. I remember feeling like the world was spinning. I remember hating the lights. I remember wanting to sleep, which I did a lot.

Recovery

Late Friday night they moved me from the PACU to the Neurosciences floor. Saturday is a bit of a blur too, but I was definitely more with it than I was in the PACU. There were visitors and flowers mixed in among the vitals checks, finger sticks, and medications. Even though I was still hooked to the IV, they took away the catheter, the bulb at my belly button and the heart monitor. That helped a lot. I started to focus more on the donut around my head.

My hair was up in a knot, Pebbles Flintstone style, with a bandage wrapping around my head. There was a hard plastic piece over my right ear wrapped in more bandages. It was heavy. I felt like a bobble head anytime I tried to move, a sensation definitely aided by the fact that my vertigo was intense. My doctors warned me that the vertigo wasn’t going to go away with the surgery and was likely to get worse before it got better: they were right. I also struggled with my vision for the first few days after surgery. I had a hard time focusing and found things to be more blurry with my contacts in than my glasses. Combine my need for glasses with the bandage around my head, and I had a problem, thus I spent my hospital stay with glasses taped to my face.

I spent a week in the hospital following the procedure, which was an interesting experience in its own right. I had a constant stream of visitors, and was never alone, which helped tremendously to keep my spirits up. I fully utilized my ability to request quiet time for everyone so I could drop off for a nap. Soon I itched to get out of bed and walk, and I was surprised at how difficult it had become. Since my sense of balance was damaged, I wobbled and lurched around like I had consumed a few too many beers. I put my visitors to work, helping keep me upright, while I leaned on my IV pole and walked up and down the hallway in my slipper socks.

Hospitals themselves are ironically not restful places, particularly the neuro floor. The beds are pressure sensitive, so the nurses can tell if patients are getting up on their own when they aren’t supposed to be. Apparently this happens all the time, prompting a stream of running feet as nurses rush to make sure no one falls over. Getting woken up every four hours for a vitals check, and finger sticks to check my insulin levels wasn’t conducive to sleep either. With the bandage on my head I was unable to shower. After a week in the hospital, this was not exactly pretty, though I tried my best to clean up and feel normal (never really successful, but I tried.)

A week after the surgery, they removed the bandage and I was cleared to leave. The vertigo continued intensely, and traveling even the short distance between the hospital and my apartment was rough. I spent a week at my apartment in Boston with my Mom taking care of me. I was still having trouble walking around without tipping over, and I was unable to do things like wash my own hair. I napped a lot, but everyday spent more hours awake and more time on my feet.

Friday April 11, my stitches came out. As I celebrated this milestone, I frustratingly also developed a seroma, a build-up of fluid around my belly button incision. I found out this is also a common complication from liposuction. The sudden onset of swelling was really unnerving, but my doctors answered my phone calls late on a Friday night to set my mind at ease. I can’t say enough good things about my doctors. What times we live in when you can text a surgeon a picture of your belly at 10:30pm on a Friday and get a helpful, calming response.

Even with this complication, my doctors have said they are happy with my progress. I know it will be a long time before I can say I feel like myself, but that is the goal I am working toward.

Part One: Diagnosis

What follows in this three part series is a personal narrative. All of the decisions I’ve made about my health were chosen in close consultation with medical professionals. My choices are mine, and not necessarily right for anyone else even with the same diagnosis. If you have concerns about your health I encourage you to seek out a medical professional, which I’m not.

“When you hear hoof beats, think of horses – not zebras,” is a widely known version of a quote attributed to Theodore Woodward, MD, late professor at the University of Maryland School of Medicine. He said this as a means of instructing medical interns to look for the most obvious, and likely, diagnoses first. The most obvious answer to a problem is usually the one that is correct, but not always.

I’ve been thinking about this quote a lot over the last year or so, like a mantra. Think horses. It’s just a headache, you sit at your desk too much. Think horses. It’s only a little dizziness, vertigo? You don’t get enough sleep. Think horses. Your right ear is ringing, an infection? Think horses. Think horses. Think horses.

Working as close to cancer research as I do can make you a little paranoid. I try hard to stay grounded, and remember that headaches are headaches for the same reason that hoof beats normally signal horses – it is simply unlikely for a headache and a little dizziness to be a harbinger of anything more.

My symptoms were easy to downplay, but when I started to pay attention to what my body was trying to tell me, it was much more than a headache and a little dizziness. It was a piercing headache radiating from the back of my skull and wrapping around the front of my head to above my right eye. It was the additional emergence of my normal migraines with a ferocious new frequency. It was vertigo that left me feeling unmoored multiple times a day, everyday. It was diminished hearing in my right ear that left me missing whole conversations, and constantly repositioning myself so people could speak on my left. It was ringing, incessant ringing, in my right ear. Eventually, it was fatigue. I typically walk 45 minutes each way to work, and I hit the point where I dreaded having to get myself to the office.

Of course, all this did not hit at once. It built up over the course of several months while I berated myself for worrying and reminded myself to think horses. I often joked with a colleague about the rare diseases I must have, things it’s absurd to think an otherwise completely healthy, 26-year-old would have. I kept expecting things to get better, like if I made it through the winter I’d magically start feeling like myself again (because that is clearly how the world works). I didn’t.

I’m really not making it up

The real drama started in February when my hearing loss had become a serious concern. I went for a hearing test that I passed, registering in the normal range. When the doctor who gave me the results told me I was fine, I stared at her in disbelief. I tried to explain that I couldn’t hear conversations that I couldn’t make out music and lyrics when my headphones were in my right ear. I tried to explain that identifying words was different from identifying tones like in the test, but the doctor just looked at me and said, “I trust my data.” As if I’m just making it all up.

Since I passed the hearing test, I wasn’t sure what to do next. So, I spent a few more weeks with the symptoms getting worse to the point that I was having migraines everyday, and actually didn’t go to the office because I was exhausted. Then, it was my tongue. I find it almost funny that my tongue was the conclusive sign something was wrong, but it was. It was numb, and I tasted metal. The migraines had sent me to my primary care doctor in mid-March, and at this appointment after I detailed all my symptoms, she asked me, “Are you feeling anything else?”

Completely as an afterthought I added, “My tongue feels weird.”

“Weird, how?”

“Numb? I guess? I’m acutely aware that I have a tongue. Does that make sense? I feel it, but only half of it. And everything tastes funny, but only funny on the right side.” (Obviously, at my most eloquent.)

To my doctor’s credit, she didn’t let her concerns show, and since she was calm I was calm. She told me later when I mentioned my tongue she knew something was seriously wrong. She recommended I go for a CT scan of my head the next day. I took that day off work, and went for the CT in the early afternoon. It was quick and painless; I left the hospital around 3pm and took a cab home.

I intended to go to work the next day since they weren’t going to find anything and all this was just to rule things out because, well, horses. I didn’t entertain the idea that my joking about rare diseases may have had merit. I called my older brother, and told him explicitly, the idea that the doctors would find something on the CT was silly, and I was going to be fine. Later that night my phone rang it was my doctor calling at 8:30pm with the CT results. It probably goes without saying that your doctor doesn’t call you personally at 8:30pm with good news.

There are four ventricles in the brain. These ventricles are hollow cavities filled with your cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) the fluid that surrounds your brain. My fourth ventricle, the one at the back of the head, was compressed, putting pressure on the flow of CSF – but the CT didn’t show what was causing the compression. My doctor told me to go to the ER immediately, because I needed an MRI. Even then, I was completely rooted in denial. My health has been my privilege, I have never had any other medical problems, and I have a clear family history. It felt silly and paranoid to think it was anything bad.

In the hospital

Since I needed to get myself to the ER, I called a friend. I don’t have any family in Boston, but my friends are incredibly supportive. When I called and said I needed a ride to the ER, the response was, “I just have to put on pants.” Another friend met us there, and we were taken back quickly. After a brief bit of confusion about why we were there (my appendix is just fine where it is, thank you) I was told I needed a consult from neurology.

In the ER that night I saw two nurses, and three doctors (or four, around 1am I got kind of fuzzy, and I don’t remember any of their names). I did a lot of touching my finger to my nose and following the light with my eyes. I cracked jokes with my friends. We discussed the upcoming nuptials of another friend and the hotly debated issue of the wedding date. I wished I had sweatpants because those gowns leave a LOT to be desired. I wondered when I would get the MRI so I could get out of there and go home.

Around 2am, I was told I was being admitted. I felt silly about it, like, I’m fine, horses and stuff, we’re just ruling things out this is not necessary. I just wanted to go to sleep. I kept getting asked if I had questions. I should have questions, shouldn’t I? I was too tired for questions. So, I just let them push me through the hospital to the neuro floor (riding a bed with wheels is a weird thing, for the record). I was incredibly concerned about the fact that I didn’t have my mouth guard to keep me from clenching my jaws, and didn’t want to sleep without it. I was assigned a room, and a nurse, and a tech. Vitals were taken for what felt like the 10th time. My friends were allowed to leave, and come back to bring me my mouth guard and a pair of sweatpants. By the time they headed home for the night, it was 3am.

My nurse woke me at 6am to get me ready for the MRI. I’m not afraid of tight spaces, and I was sleepy, so I just let them do their thing. I was back in my room by 7:30am, ordering a bagel and coffee for breakfast. My friends returned and we spent the morning hanging out as if we were anywhere but the hospital. I was texting my parents, but didn’t want them to worry since it was all a lot of fuss for nothing, so I downplayed the situation.

My primary doctor, who had ordered the CT and told me to go to the ER, came to see me that morning. It was reassuring to see a familiar face. She said they were waiting for the MRI results, and we’d know that day. Around mid-morning a group of doctors came in and asked me to go through the whole story and describe the events that had led up to me landing on their neuro ward. They said they would be back with the MRI results. My friends and I watched some mindless daytime talk shows. Then we watched the Jetsons, because daytime TV is the worst.

It was early afternoon when the doctors came back. There were five of them, ranging from medical student to the neuro attending. There was more medical history, and touching my finger to my nose. They pricked my tongue with a pin. After this, they told me the MRI results. Sitting in that hospital bed on March 19 with my friend and five doctors staring at me, I heard the words, “we found a mass.” The doctors told me that I did have a tumor, but it wasn’t a type of tumor they often see – the MRI hadn’t shown a horse, in fact, I had a zebra.

My zebra

One of the medical students (a nice guy, though perhaps a tad too gleeful about this) told me I have a type of tumor most medical students only get to see in textbooks. My tumor, in the inner ear, is called a vestibular schwannoma or an acoustic neuroma (the two are interchangeable). Your cerebral nerves pass through your brain and go out into your body to control all of your various functions. My tumor was growing on the eighth cerebral nerve (compromising my hearing) and putting pressure on the seventh (the numbness in my tongue because the seventh controls your face). It was between the cerebellum and the pons areas of my brain, and pressing on my brain stem.

Your inner ear is where your vestibular system, which controls your sense of balance, is located. Vertigo, the dizziness and spinning sensations I’d been feeling, is a common symptom of vestibular dysfunction. The location of the tumor meant that in addition to ruining my hearing on the right, my vestibular system was also seriously damaged.

According to the Acoustic Neuroma Association, these tumors affect one out of every 50,000 people and are typically diagnosed between ages 30-60. Any tumor is scary, let alone a tumor near your brain that is threatening your ability to move your face, but it also has a fantastic prognosis. I was told it is typically a slow growing tumor, so I’ve probably had it for years. These tumors are highly likely to be benign, meaning it won’t spread and become lethal. I write about neuro-oncology enough to know that operable is one of the sweetest words in the English language. I’ve had to talk to and tell the stories of family members who lost their loved ones to brain tumors that couldn’t be removed. I have never been so relieved by anything in my life as my zebra, because if it had been a more common type of brain tumor, I would face a very different outcome.

Instead, there are treatment options, all of which end with a full recovery albeit with scars. For someone like me who has had headaches and vertigo symptoms for years, I may leave all this better than I’ve ever been – this tumor needed years to grow to reach 2.4cm, and I’ve been unknowingly living with these symptoms the whole time. I decided that, for me, surgery was the best option. I felt that it would give me the best chance of never having a recurrence, and would preserve my ability to move and control my face. When I went to meet with my surgeons, they retested my hearing. The results showed that my ability to hear out of my right ear was at 56% meaning that functionally I was right all along; I couldn’t hear conversations or make out words. Since the nerve damage to my hearing would not recover, I chose a translabyrinthine approach to the surgery, which cuts the eighth nerve making me deaf in my right ear. This was a heavy decision, but when I considered all the choices my parents, surgeon, and I agreed this was most likely to give me the best outcome.

I was told that the timing of the surgery would be my choice, because this type of tumor was so likely to be slow growing, so I made plans to be away later in the month. My doctors asked me, while I processed things and made plans for my upcoming absence, to make sure to tell them if anything about my condition changed, particularly with regard to the feeling in my face. Since the tumor was seriously threatening the seventh cerebral nerve, the secondary goal for the surgery to remove it was to save that nerve. It could be the difference between having half my face paralyzed, I was told, and being completely normal. I kept being assured that I had time.

A week after I was diagnosed with an acoustic neuroma, on March 26, I woke up unable to feel half of my face. On my right side, from my cheek to my chin, everything was numb.

Thoughts Before Scio14

“I’m fine” is one of the easiest lies to tell someone. In the past year it’s a lie that I’ve told often. Mostly because it is the path of least resistance to smile, respond politely that everything is status quo, and then change the subject or simply move on. It limits the possibility of being asked questions I don’t have the answers to, or making someone who really did not want to hear my latest tale of woe really uncomfortable. Yet, 2013 seems to have presented several stretches of time when things were anything but “fine.”

With Scio14 on the horizon, I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about who I was and how I felt attending Scio last year, and where things stand now. Last year I was so excited, and incredibly optimistic about what 2013 might have in store. The conference captured all of that and added fuel to my fire; it made me feel like I could do ambitious things. I met people who were inspiring, and I felt like I belonged (which doesn’t come easily.) It was basically the high-point of last year.

I’m currently at a point in life where I feel like I need to decide what is work and what is for fun, and while I’ve reached some conclusions about how I want to spend my time, I hope attending Scio14 gives me some clarity on others. I’m a science writer professionally, but in 2012 and 2013 I also spent a tremendous amount of my free time (and savings) attending scicomm conferences, networking, writing blog posts, reading and talking to people on Twitter. I attend ScienceOnline (and many other things) completely out of pocket, on vacation days. Yes, in 2013, you folks were my vacation.

I hate getting asked what my hobbies are, because until last fall, scicomm WAS my hobby. I invested a lot of myself in these activities outside of my working hours because I enjoyed them and I thought they were valuable. It was all scicomm all the time with a little bit of friends and family thrown in. I wrote in September that I had lost heart in my online scicomm activity, and while at the time I had some renewed enthusiasm, that spark has nearly been extinguished. It isn’t just that my online scicomm feels different – it’s that I’m different. I’ve always thought that you shouldn’t write blog posts just to write blog posts, because you have to want to be a part of this – and there is a big part of me that simply doesn’t want to do this anymore.

When I think about the things that have had the most influence on how I think, and how I approach the world, 9/11 sits at the top of the list. Last year gave it some company. While I didn’t see it at the time, April is really where 2013 went off the rails for me. I didn’t think the Boston Marathon bombing affected me all that much; after all it was no 9/11. My Dad was a first responder to 9/11, he survived, but it hit us at home – it was personal. I was only 13, but I remember remarking to a classmate that day that nothing was ever going to be the same again, and it certainly wasn’t.

What happened at the Marathon shouldn’t be compared to other events, and drawing such comparisons can be problematic anyway. Still, I have come to believe that the severity of an event like this shouldn’t just be measured in lives lost or in people injured, but in fear. Fear is a deeply personal experience that affects everyone differently, yet I feel comfortable saying that an event like the Marathon bombing spreads fear like a plague. I also think that terror is its own brand of fear – a fear that for me is hauntingly familiar. Though it was different at 25 compared to 13, I still know that fear.

After the bombing I saw a lot of friends struggle with their emotions, the shattered sense of safety, the “how could this happen,” the “who would do something like that.” I didn’t have those same struggles. What kept me up at night were not the nightmares, it was the knowledge that you can try to move on, even think that you have, and still the fear – and those who spread it – will be back. It is simply a condition of being alive that we will consistently find ourselves grappling with fear – but admitting that we are scared of something can be so difficult.

When I think about what scares me the most, I come up with being powerless. I hate the idea that when people I love are in danger, there truly may be nothing that I can do to help. Looking at the world this way – with the fear that anyone you love can meet harm in an instant, and you will be powerless – it is hard for me to understand how anyone ever finds ‘peace of mind.’ I don’t really understand how in a world where shelter-in-place is a common term, everyone isn’t loosing their shit every minute of everyday. But you have to meet the fear somehow, the only other choice is to let it paralyze and consume you.

I find it hard to admit that 2013 changed me so much because of fear. I hate the idea that fear has any power – but I’ve found that it changes an awful lot. Things that seemed important before aren’t, things I wanted before I don’t , my goals have changed, and I’ve changed. So what does any of this have to do with scicomm or attending ScienceOnline? Mostly it is just to explain that I’m approaching Scio14 with a very different mindset than I did for Scio13. How I am involved in scicomm and what role I let it play in my life is something I’m re-evaluating.

This is something I was struggling with when the scicomm “community” imploded in October. After everything that happened, (which if you read my site, you know about, so I’m not going to rehash, and if you don’t know…Google) I withdrew from online scicomm even more. It’s fear again. Fear that I’m a poor judge of character. Fear that people you trust aren’t who you think they are. Fear that I don’t deserve to be here, not now, and maybe I never did. Fear that now that people are actually listening, they will notice that I never belonged.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about my life, and while I can’t claim to have had any major revelation, I have seen that how I spend my time is one thing that I can control. I want to be more thoughtful about it, and a big part of that is scicomm outside of working hours. I still think online scicomm has tremendous value, but I need to figure out how much of my life should be devoted to it. I really think it is time to get some new hobbies. I’m not writing off ScienceOnline, I still intend to manage ScioBoston and I have no plans to kill my blog or twitter completely, but I don’t intend to maintain them with any consistency either.

My main goal for Scio14 is to come away with a better idea of how to run ScioBoston effectively, and figure out how my work in development can fit into the scicomm ecosystem. I’m looking forward to finding what I hope are answers in the many conversations that will take place. I’m looking forward to seeing friends and making new connections. I also find it scary and intimidating in a way that I never did before. So, here’s to not letting fear win. See you at Scio14.

Scientist of the Month Jan 2014:Bryan Clark

Hi Everyone! I am so happy to be able to introduce you to our January scientist of the month, Bryan Clark. (I’m sorry for being late, I know January is almost over!) Bryan is a researcher who studies poisons for a government group called the Environmental Protection Agency. You can read his guest post Q&A below, and if you have any questions for him be sure to leave them in the comments.

Guest post: Bryan Clark

What type of scientist are you?

I’m a toxicologist, which means I study poisons. Toxicologists study a lot of different types of chemicals that can be poisons, from pesticides (the chemicals used to protect crops or your house from insects or weeds) to new medicines that have to be tested to make sure they are safe, to the exhaust that comes out of cars and factories (and many more). Some toxicologists mostly try to understand how chemicals affect people, but I am an ecotoxicologist – I study how the chemicals that humans produce affect wild animals. Also, I am a mechanistic toxicologist, which means that I don’t just try to find out how much poison in the water will make a fish sick or kill it, but instead I try to learn how the chemical causes the changes inside the fish’s body that can cause it harm.

It takes a long time (or at least a lot of school) to become a scientist. What is one of your favorite memories from school or things that you learned while in school?

In elementary school we learned about raptors (birds like owls and hawks) from the county naturalist, and she brought us owl pellets. When raptors eat something like a mouse they swallow it mostly whole because they don’t have teeth to chew it, but they can’t digest the bones. The bird packages up the bones and other indigestible parts into pellets and regurgitates them (kind of like throwing up). Scientists use the pellets to learn about what kind of food the raptors have been eating. The naturalist let us pick the owl pellets apart, and we were almost able to put together a whole mouse skeleton from the bones we found!

Bryan and a former labmate (Dr. Cole Matson) collecting mummichogs at a polluted site in Portsmouth, VA. Courtesy of Bryan Clark.

Another great memory is from when I was in graduate school. I was working with a team of two other researchers trying to develop a tool for controlling genes in living fish eggs. It had never been used in wild fish like the one we studied. The team had spent years trying to get it to work, and we were getting close to giving up and moving on to other things. One day I was sitting in a dark room, staring into a microscope expecting to see a bright red glow in a mummichog egg that we had treated (which would mean that it still wasn’t working). Instead, I saw almost nothing! After checking to make sure I had actually turned on the microscope, I ran down the hall to high-five my teammates because we finally succeeded.

Where do you work, and what do you do on a typical day at work?

I work at a research laboratory in Narragansett, Rhode Island that is part of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (the EPA). The EPA is the part of the government that is in charge of keeping the air you breathe and the water you drink clean and safe.

Two mummichogs embryos with a chemical that glows red collecting in their urine. Courtesy of Bryan Clark

I study populations of a small fish called the mummichog that have evolved to survive in extremely polluted places where other fish can’t live. The pollution at these sites is so bad that even a small amount of mud from the polluted site will very quickly kill fish that didn’t grow up there. I am trying to learn how the fish have adapted to survive this severe pollution. On a typical day, I spend a lot of time reading about the results of other scientists’ experiments and planning new experiments with my labmates. Then I do those experiments in the lab, which these days means trying to learn if the adapted fish have a unique version of a gene that interacts with chemicals inside the fish’s cells (we have the same gene in our cells). I also visit our fish in the lab. We have an amazing fish room that pumps seawater straight from the bay, and we have many fish from all over the Atlantic coast living in the lab (we even have some from New Jersey!) Throughout the year I also get to go to the estuaries (places where freshwater and saltwater mix) and catch new mummichogs to come live in the laboratory. A lot of our research is about how chemicals affect the young fish while they are still developing as eggs.

Why did you decide to become a scientist?

Bryan using a micromanipulator to inject an embryo (< 1 hour old and only 2 cells) with a gene function blocking agent called a morpholino. Courtesy of Bryan Clark

I have always wanted to know how things work, especially living things. As I grew up, I learned that this is basically what scientists do – they try to learn how everything works. I was also lucky that both of my parents are scientists and I got to “help” with experiments when I was very young. My father is an ecologist; when I was in elementary school I got to ride along while he tracked radio-collared raccoons using a big antenna on the roof of a pickup truck. That’s when I realized that as an environmental scientist I could study science and spend a lot of time outside and around animals. I couldn’t imagine anything better!

What is your favorite thing about your job?

I get to work with and learn from really smart, fun people while researching things that are important for keeping our planet clean and safe.

What is something you’ve found about either being a scientist or the subject you study that you think most people don’t know?

I think a lot of people don’t realize how creative scientists are. Many people think that science is just boring, repetitive, and all about learning lists of facts, but those facts are really just the building blocks that scientists use to help them reach new discoveries. Research scientists are usually trying to discover something that no one else in the whole world knows, which requires a ton of creativity. To make discoveries, scientists have to look at the world in a whole new way and think of questions no one has ever asked before. Often, scientists study animals and places and other things that no one else has ever studied or create a specialized piece of equipment that doesn’t exist anywhere else.

What are some of the things you like to do for fun?

I like all kinds of outdoor activities, especially camping, hiking, hunting, canoeing, and fishing (I don’t just do it for work!). I have a great golden retriever who comes with me on most of my outdoor adventures. I also like to play team sports; soccer is my favorite. I really like cooking too, which actually has a lot of similarities to doing scientific experiments. Like many scientists I know, I drink a lot of coffee, so now one of my hobbies is roasting my own coffee from green coffee beans.

Thank you Bryan for guest posting as the January scientist of the month! The scientist of the month segment was inspired by the stories shared on the twitter hashtag and tumblr I Am Science.

Scientist of the Month Dec 2013: David Shiffman

Hi everyone! I’m a little late with the December scientist of the month, because we did things a little differently this time. Normally, I ask a scientist who volunteers via Twitter a couple of questions, and my buddies in Mrs. Podolak’s first grade class will go over the interview, talk about it, and come up with their questions. They pose the questions in the comments, and the scientist answers them directly. You can see examples from earlier this school year here.

While this is a fun and productive set-up, this month I was able to connect our scientist David Shiffman, directly with the class over Skype. So, rather than post an interview with David, I’m just going to tell you a little about who he is, his science outreach activities, and recap a few of the questions the students asked him.

David is a marine biologist studying sharks through the RJ Dunlap Marine Conservation Program at the University of Miami. From the lab’s website: “The mission of RJD is to advance ocean conservation and scientific literacy by conducting cutting edge scientific research and providing innovative and meaningful outreach opportunities for students through exhilarating hands-on research and virtual learning experiences in marine biology.” Essentially, their focus is ocean science, but the lab and its members are also concerned with conservation, technology, and education.

The last piece, education, is why I asked David to Skype with the class directly – he’s a pro at it! In addition to being a scientist, David is also a prolific science communicator; he blogs at Southern Fried Science, and is active on Twitter @whysharksmatter and Facebook. He provides a scientists’ point of view and expertise about shark conservation for mass media outlets like Slate, Wired and Scientific American. Additionally, he regularly works with students of varying ages, answering questions about sharks and ocean conservation. Including Mrs. Podolak’s class, David Skyped with an estimated 500 students in 2013!

So what kinds of questions did the first graders ask him about sharks? I’ve listed a few below, with David’s answers.

- How many sharks are there in the world? Answer: There are over 500 different species. There have been new species discovered every two weeks or so for as long as you guys [the students] have been alive due to advances in deep sea exploration.

- How big can sharks grow? Answer: The smallest shark is about nine inches long, and the largest (a whale shark) is twice the size of a school bus. It is also the largest fish in the world.

- Do stingrays sting sharks? Answer: Yes, the stinger on a stingray is a defense mechanism. Sharks are one of the few predators of stingrays, which means that they do sometimes get stung.

- When did people first discover sharks? Answer: Aristotle wrote about sharks in ancient Greece. Scientists also know that sharks were around 250 million years longer than the dinosaurs.

- Why does a hammerhead shark look like it does? Answer: Hammerhead sharks have two extra senses. One, called ampullae of lorenzini, are jelly-filled pits on the nose that are sensitive to electricity and allow them to detect animals that are hiding under the sand. The other is a lateral line that detects vibrations.

These are just a few of the many questions that David answered for the students during their Skype interview. If you are interested in having David talk to your own students, or have a question for him you can contact him at whysharksmatter@gmail.com or on Twitter @whysharksmatter. Thank you, David for being our December Scientist of the Month!

Also: shameless plug for this segment, but if you’d like to be one of our Scientists of the Month, I’m currently accepting volunteers for 2014! I alternate months between men and women; you don’t have to be a PI or have your own lab, and I’m open to featuring any science field. You can contact me on Twitter @erinpodolak.

Adventures at the Mütter Museum

When I take trips that aren’t for conferences, I am usually lucky enough that my family and friends will indulge me and let me divert us toward nerdy activities (like when I dragged my family to the La Brea Tar Pits.) That was the case a few months ago when I visited my friend Liz in Philadelphia. When she asked me what touristy things I wanted to do, my response was, “so, there is this museum…”

I was talking about the College of Physicians of Philadelpia Mütter Museum (which is marking 150 years in 2013!) On the trip down I had been reading a book called Wicked Plants by Amy Stewart (which is a fun, quick read – if problematic plants is the kind of thing that sounds interesting to you.) At the back of the book is a list of locations that have cool gardens, the Mütter Museum was listed because in addition to the museum’s collections it also has a garden of medical plants.

Reading about the Mütter Museum intrigued me. It is a medical history museum that contains anatomical specimens, models, and medical instruments displayed in a way that harkens back to the 19th century “cabinet of curiosities. ” It was serendipity that I was reading about the Mütter, just happened to be in Philadelphia, and was with a friend whose response to my entreaty that we go look at skulls was, “oooh, let’s do it.”

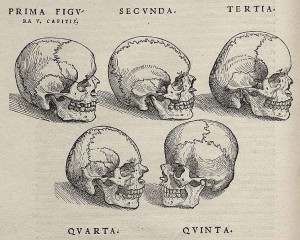

In general what I loved most about the museum was just the feel of the place. It is a little known fact that I actually love history, particularly medical history. One of my favorite classes that I took at UW-Madison was on the history of the scientific book. My main project in that class focused on evaluating an original copy of Vesalius’ de humani corpis fabrica (On the fabric of the human body) which in 1543, rocked the world of human anatomy. I was blown away by the gruesome beauty of the illustrations in Vesalius’ textbook, and spent much of my time in the library’s special reading room imagining what it would have been like to see such scandalous images when they were first published.

One of the things I love about history is being able to observe the process of discovery, how did we come to know what we know, is a fascinating question to me. The Mütter just has this air of the raw, gritty, exposure needed to understand ourselves. I found myself instantly drawn in by that quality, by the history of the place. Once fully inside of course there was the whole curiosity aspect. The specimens in the Mütter range from the relatively normal like the wall of skulls, to standard medical conditions like cancer or bone abnormalities, all the way up to the toxic megacolon. Oh, yes. I said toxic megacolon, and it is precisely what you expect a nine-foot-long human colon to be – gross and amazing.

The collection also includes specimens that radiate a slightly sad sideshow quality, like the skeleton of someone with gigantism next to someone with dwarfism. I couldn’t help trying to imagine their lives. I was also particularly struck by a skeleton with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, a condition where muscle turns to bone. While the “stone man” certainly fits the idea of a spectacle, it really hit me that this isn’t a historical disease it is a disease caused by a genetic abnormality with no known cure that can still occur today – even if it is incredibly rare. I was looking at the skeleton of a man who lived and died with that disease.

I recently wrote about the New England Aquarium and how science centers and museums can be the gateway to drive people toward science. I think this was reflected a bit in the Science Spark thread started by Ben Lillie on Twitter recently, which had people tweeting what got them involved in science. A lot of it had to do with parents, teachers, books, and movies, but a few tweets I saw had to do with trips to museums and science centers. There is a difference though, between hands on museums like Boston’s Museum of Science, and a place like the Mütter (aside from the fact that maybe skulls and preserved organs are not for small children.)

I recently received the criticism that as a stereotypical millenial, I’m only focused on the next app. While I am undeniably in the generation referred to as millenials (I may have scored a 94 out of 100 on this Pew Center quiz, for whatever that is worth) I think that characterizing whole generations in any way is a little unfair. Yes, I tend to focus on what we can do that will be new and engaging and make science and communication better – but despite how I may represent myself sometimes that doesn’t mean I disregard the past completely. I don’t think you can consider the future in a productive way without reflecting on where we’ve been. That was part of what I loved about the Mütter, it didn’t spark me as a gateway toward science, it sparked me as a cause for reflection. It made me think, and it made me feel. It stirred up my brain. That, to me, is one of the most valuable things about preserving our history.

I mentioned that I went with a friend to the museum. My friend is a perfect example of an interested but non-sciencey audience. Her response, when I asked her what she thought, was that the Mütter left her feeling a good kind of disturbed. She liked the museum, but it made her a little uncomfortable, in a way that perhaps only such an up close look at the corporeal things that make us human can make one feel. I am a science minded person, but I felt that way too. For both of us, it was an afternoon well spent.

If you find yourself in Philadelphia, I whole-heartedly recommend a trip to the Mütter Museum. It is also worth mentioning that the museum is currently running a “Save Our Skulls” campaign where you can adopt a skull from the Hyrtl Collection for $200. For more on Joseph Hyrtl and the pseudo-science of phrenology, check out this Wired article by Greg Miller. You can also check the museum out on Twitter @muttermuseum or visit their YouTube channel.

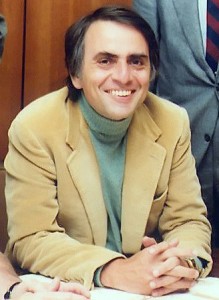

Can We Stop Talking About Carl Sagan?

Update #3 [Up at the top, so that hopefully people read it.] Does the title of this post make you angry? Well, you’re not alone. I continue to hear from many people who think I am downright stupid for daring to ask this question. Seeing all the backlash, I’ll be first to admit that I wish I had titled it something less provocative (even though it didn’t feel all that provocative at the time.) All I want to suggest is that we hold up some other examples of good science communicators, I don’t want to, or think that we can, erase the past. Sagan has a deity-like position for some people, and I didn’t do a very good job of explaining why that makes me feel so bad sometimes. I wanted to offer a different point of view. As was said to me on twitter, we should recognize Sagan the way we recognize Da Vinci, Einstein, Galileo – as greats. That doesn’t mean we should let that stall our ability to move forward and try to make new great things, with new great people.

Update #4 You know, the moment I had to ask my Mom (because my computer was giving me trouble and I couldn’t log into my own site – go figure) to log in to this site to respond to a comment to say that I don’t think Sagan hated women kind of made me want to give up completely. But I’ve read two thoughtful responses to my post, and I realized that the main thing I’m not saying is why I felt the need to write this in the first place. When we hold up Sagan again and again as the greatest there ever was, when we take his quotes and put them on pretty pictures that go viral, when the TV special continues to live online, when we talk again and again about how this one person inspired humanity and made people see that science is human – and all of it makes me feel nothing, I can’t help but think that perhaps I’m less than human. I joked with a friend yesterday that perhaps I’m just dead inside, but it isn’t really a joke to me. If Sagan represents all that is good, and I don’t understand it, then I can’t be good. So, if you want to know where this post was written, it was written from a place of fear and self doubt.

I am hopelessly optimistic about life to the point of near desperation to find the good in everything. So I thought, well, if I feel this way, other people must too. I warped that thinking into the blanket statements that caused so much of the trouble in this post. I know better than to publish without letting something sit so I can rethink it, and I broke my own rule, and made a mistake here. Some people have reached out to me to say they shared my feelings. So, to those people, I hope knowing you aren’t alone in not feeling so inspired makes you feel better.

My problem isn’t really with Sagan himself, and I didn’t do a good job of explaining that I take issue with the culture surrounding Sagan, with the way he is idolized as a one-and-only, with the vehemence of some of his fans. People have told me he would also promote women and diversity, which is a good thing. I do still think that other examples are needed not just to show a different approach to science communication, but to show different people to encourage other people that they can do this, even if they don’t see themselves in Sagan.

To everyone who challenged me to refine my thinking and more clearly state my point of view, you are everything I love about the Internet and I thank you for keeping your calm demeanor and engaging with me in a productive way. To everyone who called me stupid, self-absorbed, uneducated, and told me to learn my place, to learn some “respect, baby” well, I don’t particularly know what to say to you, but I hope you feel better too. To those who accused me of having no appreciation for the past, disrespecting my parents (what? – I felt so bad about that I even asked them, and they laughed at me) and wanting a world of nothing but listicles and Honey-Boo-Boo and instant gratification – that wasn’t the point I tried to make, which I admit to failing to make the first time, and I hope you’ll think again about what I’m actually asking us to do.

If what the world really needs are more and more Sagans, I guess I may be out of a job. But, I continue to think that I don’t really want to try to be anybody else, that’s the whole problem with idol worship, and I just want to try to make my own good things. Quite frankly, I don’t think we even CAN have another Sagan – it’s a very different world. I hope that in holding up other people as examples we can drive home the idea that there is more than one way to do something, more than one way to reach people, more than one way to do something good.

I also want to say that to those that called me out on categorizing Sagan based on his appearance, you’re right that I hate when it gets done to me, and as frustrating as I can get about it, it is still not right to categorize someone else that way. It wasn’t a productive way to have this conversation. If I offended you, but you kept quiet about it, you have my sincere apology too. The body of this post is largely intact, all of my flaws and all, so you can read the original below along with the other updates. I would also encourage you to read the response posts here and here.

It feels like I’m committing an act of science communication sacrilege here, but I have a confession to make: Carl Sagan means absolutely nothing to me. No more than any other person from my parents 1970’s yearbooks that could rock the turtle neck/blazer combo with the best of them. There, my secret is out.

[This paragraph is edited] I’m not saying I don’t like Sagan – I’m saying Sagan has zero influence on me or what I do. To me, Sagan is a stereotypical scientist who made some show that a lot of people really liked more than 30 years ago. That show – Cosmos: A Personal Voyage -was on air nearly a decade before I was even born. The reason I bring up my own age is because I’m as old, if not older, than the prime audience for science communication. I think anyone can learn to appreciate science at any age in life, but we stand the best chance at convincing people that science is something they can understand (and even do themselves) early in life when their beliefs are not so entrenched.

So then why, WHY as science communicators do we keep going around and around among ourselves about how Sagan – who is so far outside my life experience, let alone that of people younger than me – was the greatest science communicator of all time? We keep talking about who will (or won’t) be the next Carl Sagan but I promise you, no high school kid cares about Carl Sagan let alone whether or not science communicators think he was great. [Please see Updates #1 and #2 at the bottom of this post, to address the flaw in this blanket statement.] We spend so much time and energy talking about a guy that isn’t relevant anymore. The topics of space, the natural world, and how to communicate wonder are totally relevant to the public and to the science writing community. But, this one guy? Nope.

[This paragraph is edited] It isn’t just the age thing. I recently read Alone in a Room Full of Science Writers by Apoorva Mandavilli about the National Association of Science Writers annual meeting, and how there was a distinct lack of minorities, let alone minority women. She said:

“You can never overestimate how empowering it is to see someone who looks like you—only older and more successful. That, much more than well-meaning advice and encouragement, tells you that you can make it.”

That idea stuck with me. Role models are a great thing, and I get that Sagan inspired people to become scientists themselves. But, if we want to seriously address issues of diversity in science and science communication holding up the stereotypical scientist over and over again isn’t doing anyone any favors. I’m not trying to belittle anyone’s inspiration for pursuing science, let alone belittle Sagan himself. I respect the work Sagan did as a scientist and communicator. I respect that at the time he brought science into the mainstream in a way that hadn’t been done before. But, we need new things.

We need things that fit a modern era, things that will supplement the nerdy white dude stereotype (I mean, I generally like nerdy white dudes, you don’t have to leave, we just need other people too.) I believe that we can do better than lamenting some guy in a turtleneck as if nothing good will ever happen again. We can focus on diversity – showing men and women, of different ethnicities and backgrounds that science isn’t only for nerds.

The answer isn’t as simple as rebooting Cosmos, as FOX is doing, and sticking Neil deGrasse Tyson in front of the camera. While Tyson is far more relevant, and yes is a minority, we still need to get women, other minorities, and young people doing all kinds of science out in public view. If we want diversity we need to show people that people just like them can, and do, like science. We need everybody.

Now, I realize that instinctively we want to defend our childhood heroes. You may be sitting at your computer thinking, “but, but, you just don’t GET it, you don’t understand what a big impact Sagan had.” You are right, and that is 100% my point. I’m an admittedly nerdy, white, science communicator. If I don’t care about Sagan, do you honestly think the general public does? Science, particularly space, yes. Sagan, nope.

I sincerely hope the reboot of Cosmos starring Tyson does well, because science programming on a major television network in primetime is a good thing. I have faith that the science will be sound, and we are in dire need of an upgrade from Mermaids and Megalodons so I think it’s great. That said, I still think it is a complete waste of our efforts to keep going on and on about WHO will be the next Sagan when we should really be talking about HOW we’re going to engage with a diverse audience about science and WHAT platforms and tools will we use to be effective. To me, those are far more productive conversations to have.

The science isn’t going to stop being interesting, it isn’t going to stop being relevant – but if we can’t push our professional conversations and aspirations past Sagan, we will stop being relevant.

Bonus: I didn’t know where to include this link, but here is Hope Jahren’s Ode to Carl Sagan. You should probably read it.

Update: Well, this is easily the most talked about post I’ve ever written. Lots of feedback here and on twitter. Most prominent are the voices saying but I love Sagan, he did such good things. Rock on, I’m not saying that he didn’t. Keep your fondness for him. There are young people who find Sagan inspiring. Blanket statements like the ones I made here don’t do justice to the fact that really, what inspires you is deeply personal. To each, their own. I took a hard line stance because it feels important to me for people to feel comfortable admitting that Sagan doesn’t inspire them if he doesn’t. Again, to each their own. So, I nod to those young people who are inspired by Sagan, you’re right that I don’t speak for you, nor do I have a right to do so. But I also nod to everyone who said this made them feel better because other role models for science and science communication are something that many of us (if not all) would benefit from. Some people feel othered by not being into Sagan – if that makes any sense. But, I’m not trying to other anyone here either. I shouldn’t dismiss the significance of what Cosmos achieved, and should have included that we can still learn from what has been successful – even if I am seriously cautious about merely trying to replicate the past without pushing further, to do better.

Update #2: I wish I could change the title of this post to “Can We Stop Talking About Carl Sagan All of the Time” but it is what it is. I’m still getting comments about how wrong I am, because Sagan means so much to so many people, so to clarify: I took a very line in the sand approach in this post. I’ve talked to a lot of people since advocating for a middle of the road approach, the “we need everybody” that I mentioned. Keep Sagan, but find a way to promote others too. His popularity speaks to the fact that his work gets through to a lot of people. My blanket statements contradict that in a way that is confusing. I should have been more careful, and written about how he doesn’t get through to some people and we do need new things to get through to the people his work doesn’t reach. I don’t want us to throw away the good work that Sagan did and never talk about it ever again as if we can’t still get value from it. Keep what worked, appreciate the value added, but I still think shifting our focus to new things is beneficial.

Scientist of the Month November 2013: Elisabeth Newton

Hello first graders! I’m excited to introduce you to our new scientist of the month Elisabeth Newton. When I was a kid, the first book I read that made me fall in love with science was all about astronomy, I even still have it! I loved space, and looking up at the stars at night. While my work has nothing to do with space, it is still one of my favorite topics – so lucky for us, Elisabeth studies space!

Erin: What type of scientist are you?

Elisabeth: I’m an astronomer, and I use telescopes to learn about small nearby stars, which are called red dwarfs. Astronomers study all kinds of things in space, from the explosion of stars, to asteroids in our solar system, to the formation of galaxies. Some astronomers are like me, and use telescopes to make observations. Other astronomers use computers to try to model what we see.

Erin: It takes a long time (or at least a lot of school) to become a scientist. What is one of your favorite memories from school or things that you learned in school?

Elisabeth: It does take a long time, and I’m still in school! (Thankfully, as a graduate student in astronomy, I actually get paid to go to school, which I think is a pretty good deal.) My favorite memory so far is using a telescope for the first time, which was during my first year of graduate school. I had never used a telescope before, and the first one I used was in Chile. It was so beautiful! The best part was at dawn, when I got to watch the telescope being shut down for the day while the sun rose over the mountains.

Erin: Where do you work, and what do you do on a typical day at work?

Elisabeth: A typical day for me is spent in my office. I analyze my data, I make plots, and I read about the science other people are doing. I also spend time talking to my fellow scientists and discussing ideas for new research, or a new result that’s just come out. But sometimes I get to go on very exciting trips! I’ve been to Chile and Hawaii to use telescopes located on the tops of mountains, and to Germany and Maui to attend conferences. In the past couple of years, I also have helped to teach classes and taken classes myself.

Erin: Why did you decide to become a scientist?

Elisabeth: This is a hard one! I loved physics in high school, and I thought it was really cool how equations could help us understand how the world works. In college, I did research on galaxies and learned that I liked the day to day parts of research in astronomy: trying to understand data, writing computer programs, and writing about my results. I also enjoy teaching and mentoring students, and that’s also a big part of being a good scientist.

Erin: What is your favorite thing about your job?

Elisabeth: I’m a graduate student right now and my main job right now is to do research and learn to be a good scientist, which is pretty cool. For me, the best part about being a scientist is getting to learn about the Universe, and just being in a place where new discoveries are made every day. My friends find planets orbiting other stars, model the sun, and work to understand how galaxies form.

Erin: What is something you’ve found about either being a scientist or the subject you study that most people don’t know?

Elisabeth: The closest star to the sun is called Proxima Centauri and it’s a red dwarf star, one of the type of stars that I study. In fact, red dwarfs are the most common type of star in our entire galaxy. But they are also really, really faint: not a single one is visible by eye in the night sky!

Erin: What are some of the things you like to do for fun?

Elisabeth: The main things I do for fun are rock climbing and playing board games. Recently, I’ve been learning how to make bread, applesauce and ice cream, so I’ve had a lot of fun in the kitchen over the past few months. I also like to do arts and crafts; my favorite thing is making earrings, but right now I am trying to learn how to sew.

What do you think first graders? I hope you enjoyed reading my interview with Elisabeth, and don’t forget if you have any questions you’d like to ask her, be sure to leave them in the comments. Grown ups – if you would like to learn more about Elisabeth, you can find her on twitter @EllieInSpace. I’m always taking volunteers for scientist of the month, so let me know if you’d like to participate!

The scientist of the month segment was inspired by the stories shared on twitter and tumblr from I Am Science.

Look

This has been a hard week for everyone who considers themselves a part of the online science communication community. There has been racism and sexism, sexual harassment, and ultimately the resignation of a leader in our group. I’ve been stewing over whether or not to add my voice to those weighing in on recent events, and I decided to write because I feel very strongly about a few things.