When I take trips that aren’t for conferences, I am usually lucky enough that my family and friends will indulge me and let me divert us toward nerdy activities (like when I dragged my family to the La Brea Tar Pits.) That was the case a few months ago when I visited my friend Liz in Philadelphia. When she asked me what touristy things I wanted to do, my response was, “so, there is this museum…”

I was talking about the College of Physicians of Philadelpia Mütter Museum (which is marking 150 years in 2013!) On the trip down I had been reading a book called Wicked Plants by Amy Stewart (which is a fun, quick read – if problematic plants is the kind of thing that sounds interesting to you.) At the back of the book is a list of locations that have cool gardens, the Mütter Museum was listed because in addition to the museum’s collections it also has a garden of medical plants.

Reading about the Mütter Museum intrigued me. It is a medical history museum that contains anatomical specimens, models, and medical instruments displayed in a way that harkens back to the 19th century “cabinet of curiosities. ” It was serendipity that I was reading about the Mütter, just happened to be in Philadelphia, and was with a friend whose response to my entreaty that we go look at skulls was, “oooh, let’s do it.”

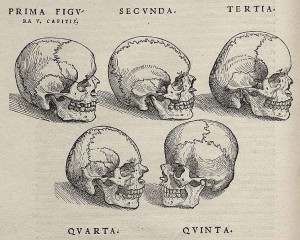

In general what I loved most about the museum was just the feel of the place. It is a little known fact that I actually love history, particularly medical history. One of my favorite classes that I took at UW-Madison was on the history of the scientific book. My main project in that class focused on evaluating an original copy of Vesalius’ de humani corpis fabrica (On the fabric of the human body) which in 1543, rocked the world of human anatomy. I was blown away by the gruesome beauty of the illustrations in Vesalius’ textbook, and spent much of my time in the library’s special reading room imagining what it would have been like to see such scandalous images when they were first published.

One of the things I love about history is being able to observe the process of discovery, how did we come to know what we know, is a fascinating question to me. The Mütter just has this air of the raw, gritty, exposure needed to understand ourselves. I found myself instantly drawn in by that quality, by the history of the place. Once fully inside of course there was the whole curiosity aspect. The specimens in the Mütter range from the relatively normal like the wall of skulls, to standard medical conditions like cancer or bone abnormalities, all the way up to the toxic megacolon. Oh, yes. I said toxic megacolon, and it is precisely what you expect a nine-foot-long human colon to be – gross and amazing.

The collection also includes specimens that radiate a slightly sad sideshow quality, like the skeleton of someone with gigantism next to someone with dwarfism. I couldn’t help trying to imagine their lives. I was also particularly struck by a skeleton with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva, a condition where muscle turns to bone. While the “stone man” certainly fits the idea of a spectacle, it really hit me that this isn’t a historical disease it is a disease caused by a genetic abnormality with no known cure that can still occur today – even if it is incredibly rare. I was looking at the skeleton of a man who lived and died with that disease.

I recently wrote about the New England Aquarium and how science centers and museums can be the gateway to drive people toward science. I think this was reflected a bit in the Science Spark thread started by Ben Lillie on Twitter recently, which had people tweeting what got them involved in science. A lot of it had to do with parents, teachers, books, and movies, but a few tweets I saw had to do with trips to museums and science centers. There is a difference though, between hands on museums like Boston’s Museum of Science, and a place like the Mütter (aside from the fact that maybe skulls and preserved organs are not for small children.)

I recently received the criticism that as a stereotypical millenial, I’m only focused on the next app. While I am undeniably in the generation referred to as millenials (I may have scored a 94 out of 100 on this Pew Center quiz, for whatever that is worth) I think that characterizing whole generations in any way is a little unfair. Yes, I tend to focus on what we can do that will be new and engaging and make science and communication better – but despite how I may represent myself sometimes that doesn’t mean I disregard the past completely. I don’t think you can consider the future in a productive way without reflecting on where we’ve been. That was part of what I loved about the Mütter, it didn’t spark me as a gateway toward science, it sparked me as a cause for reflection. It made me think, and it made me feel. It stirred up my brain. That, to me, is one of the most valuable things about preserving our history.

I mentioned that I went with a friend to the museum. My friend is a perfect example of an interested but non-sciencey audience. Her response, when I asked her what she thought, was that the Mütter left her feeling a good kind of disturbed. She liked the museum, but it made her a little uncomfortable, in a way that perhaps only such an up close look at the corporeal things that make us human can make one feel. I am a science minded person, but I felt that way too. For both of us, it was an afternoon well spent.

If you find yourself in Philadelphia, I whole-heartedly recommend a trip to the Mütter Museum. It is also worth mentioning that the museum is currently running a “Save Our Skulls” campaign where you can adopt a skull from the Hyrtl Collection for $200. For more on Joseph Hyrtl and the pseudo-science of phrenology, check out this Wired article by Greg Miller. You can also check the museum out on Twitter @muttermuseum or visit their YouTube channel.