SFSYO Scientist of the Month: Penny Higgins

Science For Six-Year-Olds (SFSYO for this school year) is a recurring segment on Science Decoded for Mrs. Podolak’s first grade class at Lincoln-Hubbard elementary school. This year the posts are inspired by #iamscience (also a Tumblr) and#realwomenofscience two hashtags on twitter that drove home for me the importance of teaching people who scientists are and what they really do.

Hello first graders! I am so excited to share with you our first scientist of the month, Penny Higgins, PhD. I asked Penny a bunch of questions to find out more about what she does. I hope you will enjoy learning more about her. Below you can read my interview with Penny, and if you’d like to ask her any questions, be sure to leave them in the comments!

Summer 2012. Courtesy of Penny Higgins.

Erin: What type of scientist are you?

Penny: I am a vertebrate paleontologist, which means I study fossil animals that have bones (fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Dinosaurs in are in this category too.) I am also a geochemist, which means I study the chemistry of geological things like rocks. These are related because bones and teeth are made of a mineral (called apatite). I study the chemistry of fossil teeth and bones to learn about what extinct animals ate and what the environment was like (how warm was it? how much did it rain?) when they were alive.

Erin: What did you study in school, and where did you go?

Penny: I studied both geology and biology in school, since fossils come out of rocks (geology) and represent animals that were once alive (biology). I also took a lot of chemistry classes. I ultimately got a PhD in Geology. I went to school in Colorado for five years, then went for another five years in Wyoming, where I got my PhD. Then I studied another four years after that in Florida. Now I live in Rochester, NY.

Erin: Where do you work?

Penny: I work at the University of Rochester, in Rochester, New York. My main job is to manage a laboratory where we measure the chemical properties of rocks and minerals. We also analyze things like hair, bugs, and flowers. I also teach beginning geology and a couple of paleontology classes. During the summer, I travel all over to collect fossils (and rocks) for my research.

Erin: What do you do on a typical day?

Penny: Most days during the school year, the first thing I do in the morning is start a set of analyses on our mass spectrometer. Then I go and teach classes, work with students on their research projects, and make sure that everyone is getting good data. When things are quiet I do my own research.

Erin: Why did you become a scientist?

Penny: I loved science from the moment I knew what it was. I was hooked by Carl Sagan’s Cosmos videos [Cosmos is an old TV series, you first graders wouldn’t know it but maybe your parents will!] I also enjoyed drawing animals, especially horses, and started to study their anatomy and the shapes of their bones. Once I realized I liked bones, I wanted to draw dinosaurs and started to study them so I could draw better pictures. That’s why I became a paleontologist. What’s funny is that, now that I really am a paleontologist, I’ve never done anything with dinosaurs, but I have looked at fossil horses!

Courtesy of Penny Higgins.

Erin: What is your favorite thing about your job?

Penny: My favorite thing is the discovery. I learn things that no one else has ever known before. And I get to share what I learned with other people, so everyone can know more. I also get to go to some really neat places, like Bolivia, or the Arctic, where no-one else hardly ever goes!

Erin: What is something about your job that might surprise us?

Penny: I work in a laboratory, but it’s nothing like what you think. We only sometimes wear white coats. We listen to loud music. I’ve named all of the scientific instruments (Specky, the mass spectrometer; Norm, the water analyzer; Tina, the laminar flow hood). And there’s a talking chicken hanging in the lab.

Erin: What are some of the things that you like to do for fun?

Penny: Besides being a scientist, I have other hobbies. I am a writer, and I am about 600 pages into writing my first novel. It’s not about paleontology at all. It’s set in medieval Europe. I like to sew and make costumes, and then wear those costumes at Renaissance Festivals (where people dress up like it’s the time of knights and swords). I am really interested in medieval history.

***

Guest Post: Anna Tomasulo On HealthMap

This week I am happy to be hosting a post on Science Decoded by guest blogger Anna Tomasulo, project coordinator for Healthmap and Editor-in-Chief of The Disease Daily. Please note that I am not personally promoting Healthmap as a service, I just think it is an interesting case-study of the way the internet can be harnessed to gather data in real-time so I asked Anna to give us some background.

Book Review: The Emperor of all Maladies

Due to my new job as a writer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute I now find myself writing on a cancer biology beat. I feel like there are two ways to cultivate a beat, either you can grow into a beat by developing the background knowledge and sources over time, or you can be tossed into a beat and have to do your homework very quickly to get up to speed. Obviously, taking a job at DFCI forced me to take my basic knowledge of cancer research to a higher level very quickly.

I still have a long way to go before I’ll feel comfortable with my cancer bio knowledge, but I’ve learned a lot from all of the great articles and books I’ve been reading over the last two months. One of the books I read on the recommendation of a colleague who said it really helped her when she started on this beat, was The Emperor of all Maladies: A Biography of Cancer by Siddhartha Mukherjee. A former DFCI fellow, Mukherjee is a physician, scientist, and writer. He wrote The Emperor of all Maladies in 2010, and it received a tremendous amount of acclaim including the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.

Very rarely in a book review do I say that I think everyone should read a book. More often I recommend books with caveats that if you aren’t interested in the subject matter, don’t like nonfiction, have trouble staying focused, etc perhaps you won’t enjoy a book as much as I did. I am recommending The Emperor of all Maladies for everyone, regardless of what you normally read or are typically interested in. This book, and Mukherjee himself, deserve every ounce of praise that has been heaped upon them. There is a lot of information in The Emperor of all Maladies, and depending on how and where you read it might take you a long time to get through. It will be worth it.

Very rarely in a book review do I say that I think everyone should read a book. More often I recommend books with caveats that if you aren’t interested in the subject matter, don’t like nonfiction, have trouble staying focused, etc perhaps you won’t enjoy a book as much as I did. I am recommending The Emperor of all Maladies for everyone, regardless of what you normally read or are typically interested in. This book, and Mukherjee himself, deserve every ounce of praise that has been heaped upon them. There is a lot of information in The Emperor of all Maladies, and depending on how and where you read it might take you a long time to get through. It will be worth it.

I learned so much from this book, not just about cancer but about how to tell a long, complicated narrative in a way that is factual while still compelling. The patient narrative that the book starts and ends with brings a personal touch to the book, but the physicians, activists, and researchers interwoven into the story by Mukherjee also make this a deeply personal story. I think one of the biggest achievements of this book is being able to meld science and history to provide a foundation for the cast of characters that drive home the human impact of cancer.

The Emperor of all Maladies is masterful at doing something that so much science writing on the web and elsewhere fails to do – it provides background and context for all of the claims that it makes. Granted, developments that have advanced our knowledge of cancer biology aren’t particularly controversial, but it is still necessary to illuminate the scientific process and make clear how these discoveries come to be. This book is just solid in so many ways. The structure is great, and very effectively drives the narrative forward. The personal stories add so much to the overall understanding of cancer and its impact. The science and medical information is clear and easy to understand.

There is just so much that you can learn from this book. I don’t think I’ve come across another resource that was as interesting and entertaining while being as informative about all of the issues involved in cancer than this one. I recommend it to everyone because cancer is something that affects us all, if you don’t have it yourself then you know someone who has had to face that diagnosis. The Emperor of all Maladies really is a biography of cancer, and the crash course that I think we all could stand to go through for a better understanding of this disease.

Science For Six-Year-Olds: Introducing The Scientist of the Month Segment

Science For Six-Year-Olds is a recurring segment on Science Decoded for Mrs. Podolak’s first grade class at Lincoln-Hubbard elementary school. This year the posts are inspired by #iamscience (also a Tumblr) and #realwomenofscience two hashtags on twitter that drove home for me the importance of teaching people who scientists are and what they really do.

Hello first graders, welcome to Science Decoded! I am so excited to be writing posts just for you this school year. We are going to have a lot of fun blogging together, because we are going to have a special year-long spotlight on who scientists are and what they do. We’ll have our first Scientist of the Month in October, but before we do I first want to find out what you know about scientists.

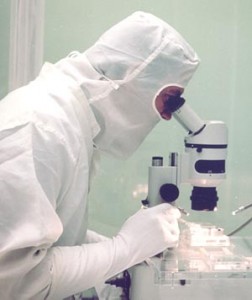

What do you think a scientist looks like? Are they all wrapped up in a laboratory like this person on the right? How would you describe a scientist? Are they smart, funny, kind, brave, patient, or happy? Do scientists get to have fun? What do you think scientists do all day? How old do you have to be to be a scientist? Are scientists boys or girls or both? Do any of you know anybody who is a scientist? What are they like?

The reason I wanted to do this segment for you is because scientists aren’t any one thing. Yes, they are all bound together by the fact that they very systematically analyze information to learn new things. But scientists are a very diverse group – they are lots of different people, with many different interests and backgrounds. Scientists also study all kinds of different things. A scientist can study plants, animals, cells, chemicals, energy, the way things move, medicine, space and how to build or put things together in addition to a lot of other stuff!

Scientists are important to all of us, because they work hard to try to figure out things about the world that we don’t know. There used to be a time when people didn’t know that all living things are made of cells, but today we know so much more about them and have learned that understanding what goes on in cells is critically important. What are some of the things that you know about that scientists have discovered? Do you know the names of any scientists?

I hope you have had a good time talking about who scientists are and what they do. I’m really looking forward to introducing you to some great scientists and helping you learn more about what it means to be a scientist. Our first scientist is a paleontologist and geochemist (don’t worry, we’ll learn what that means) but in the meantime if you have any questions for me, feel free to leave them in the comments.

I’m not a scientist, I’m a science writer. I went to school to learn how to research, report on, and write stories about scientists and what they discover. But, even though I’m not a scientist, helping share scientists’ ideas is my specialty. Hopefully, I’ll be able to do that with these posts!

The Question of Code

Earlier this week Bora Zivkovic (@boraz) blogs editor at Scientific American tossed out the following links on twitter, and asked for thoughts. Both links were to articles from the Nieman Journalism Lab, the first Want to produce hirable grads, journalism schools? Teach them to code and the second News orgs want journalists who are great a a few things, rather than good at many present two different ways of thinking about the skills journalists need to have. The links started a conversation on twitter (excerpted below) between Bora, Rose Eveleth (@roseveleth) Kathleen Raven (@sci2mrow) Lena Groeger (@lenagroeger) and myself (@erinpodolak) I felt like there was more to say on the topic, so I decided to take it to the blog so that I could respond to everyone’s points without the confines of twitter brevity.

Book Review: Newjack Guarding Sing Sing

When I try to explain to friends and family why I prefer to read nonfiction I usually tell them it is because the best stories are the ones that are true. Yes, making things up and presenting them in a way that is creative, entertaining, eloquent, and even beautiful takes skill and talent. I’m not arguing against fiction in general, I will certainly concede that there are wonderful works of fiction. There is definitely something appealing about getting lost in a made up world. However, it is my personal experience that I find myself more compelled and moved by stories that I know are real.

I’m of the opinion that what happens in real life can be so fascinating that you can be transported completely into another time and place within this world rather than the Middle Earths or Panems of fiction. We see the world from a point of view that is shaped and focused by our own experience, knowledge and understanding about the way that things work. But the scope of my world is narrow. There are a lot of things in this world that I know absolutely nothing about. In a lot of instances, this is because I have had a very comfortable life. I want to understand the rest of the world, but can you ever really understand something that you haven’t experienced yourself?

I’m of the opinion that what happens in real life can be so fascinating that you can be transported completely into another time and place within this world rather than the Middle Earths or Panems of fiction. We see the world from a point of view that is shaped and focused by our own experience, knowledge and understanding about the way that things work. But the scope of my world is narrow. There are a lot of things in this world that I know absolutely nothing about. In a lot of instances, this is because I have had a very comfortable life. I want to understand the rest of the world, but can you ever really understand something that you haven’t experienced yourself?

Vacation Adventure: The La Brea Tar Pits

Credit: Erin Podolak

Excavations of the area have been ongoing since the initial 1913-1915 project began. The 23 acre Hancock estate was officially turned over by the family to Los Angeles County for scientific exploration. The density and richness of the La Brea area is really remarkable. Several examples of prehistoric species have been uncovered at the La Brea Tar Pits including mammoths, mastadons, dire wolves, short-faced bears, ground sloths and saber-toothed cats. I think it can be easy to forget that until only 11,000 years ago North America had some tremendous large mammals that were all driven extinct. My favorites are definitely the short-faced bear and the ground sloth. By comparison, dinosaurs last roamed the Earth 65 million years ago. The last ice age dates to 0.3 million years ago. The Pleistocene, when many of the La Brea animals would have lived dates from 40,000 to 11,000 years ago. Several of the bones have been dated using Carbon-14 radiometric dating, which showed some of the oldest remains to be 46, 800 years old.

ground sloth. Or at least, that is how I felt.

What I loved about the La Brea Tar Pits was the ability to ignite a sense of imagination. I thought it was great to try to visualize what the area would have looked like some 40,000 years ago. Trying to imagine an animal like a mastodon just wandering by you as you watch tar bubbling up to the surface of the lake pit definitely peaked my sense of wonder at the world. If you find yourself in the Los Angeles area, I definitely recommend the La Brea Tar Pits as a must see for kids and adults. The museum is fun and informative and the grounds that you can walk around and peer into the pits are definitely interesting to see. Really, who wouldn’t want the chance to ride a ground sloth?

New Job: The Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

After an incredibly crazy month of traveling, interviewing, and moving I have officially started my new full time job at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. I announced on Twitter a few weeks ago that I accepted a position with DFCI as a science writer for donor relations, but I realized I never really gave my blog readers any background on what I’ll be doing. After all my whining and pontificating about growing up and joining the work force, it wouldn’t be right to not explain what my new job is all about.

As a science writer for donor relations my role is to research, gather information, and interview PI’s about research projects (mostly pre-clinical and clinical) on specific beats that I’ve been assigned. The beats are all specific subdivisions regarding research at DFCI, it could be a specific group of cancers like women’s cancers, a particular research group or institute or a particular program or approach to looking for treatments. DFCI is one of the oldest and most accomplished cancer research institutes in the United States with a serious commitment to both research and patient care.

Book Review: The Perfect Storm

I have been told by many teachers and writers more experienced than I, that one of the best ways to create good writing is to read good writing. This is a lesson I find easy to embrace considering I love to read. One of the first classes I took at UW-Madison was Deborah Blum’s literary nonfiction course, in which I spent the semester enveloped in the work of some great narrative nonfiction writers. One of those writers was Sebastian Junger, whose 2010 book War I’ve written about previously and recommend.

When I discover a writer that I enjoy I try to go back and read their other work. I’ve done this with Dave Eggers reading Zeitoun, What Is The What, and A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius. I decided to give another of Junger’s pieces a shot and added The Perfect Storm to my Summer reading list. The Perfect Storm was published in 1997, and is the book that made Junger famous. It pieces together the last days of the swordfishing boat the Andrea Gail, which disappeared during a 1991 storm off the coast of Nova Scotia with all six crew members on board. I don’t believe in spoilers more than two decades after a story breaks, so I’ll go ahead and tell you that apart from some fuel tanks and some debris the boat has never been found, and its crew drowned.

When The Perfect Storm was released Junger was called the next Hemingway. I certainly am not enough of an authority on Hemingway to weigh in about whether that is an apt comparison but I can say that Junger is masterful in the way he tells the story of the Andrea Gail. Communications on the boat were suspended in its final hours, so there is no definitive record of what happened. The last communication from the boat was on the evening of October 28, 1991. After that, what happened to the boat and her crew is open to interpretation. But interpret, Junger does. Based on research on the storm and weather patterns, about the Andrea Gail and how she was built, about swordfishing and what an experienced Captain like the Andrea Gail’s Billy Tyne would do when faced with the weather conditions Junger pieces together a likely scenario for what the Andrea Gail and her crew went through in that storm.

When The Perfect Storm was released Junger was called the next Hemingway. I certainly am not enough of an authority on Hemingway to weigh in about whether that is an apt comparison but I can say that Junger is masterful in the way he tells the story of the Andrea Gail. Communications on the boat were suspended in its final hours, so there is no definitive record of what happened. The last communication from the boat was on the evening of October 28, 1991. After that, what happened to the boat and her crew is open to interpretation. But interpret, Junger does. Based on research on the storm and weather patterns, about the Andrea Gail and how she was built, about swordfishing and what an experienced Captain like the Andrea Gail’s Billy Tyne would do when faced with the weather conditions Junger pieces together a likely scenario for what the Andrea Gail and her crew went through in that storm.

As a work of nonfiction that tells a story where no one knows for sure what happened, I think The Perfect Storm really works. Junger is honest with the readers that the only way to try to understand what happened to the ship is to understand everything else about the circumstances surrounding her disappearance. He achieves this with an amount of elegance and grace that does justice to the tragedy that unfolded while still presenting hard facts along with probable outcomes as evidence. I found the recreation of what it is like to be on a sinking ship, knowing you are going to drown to be particularly poignant.

“They’re in absolute darkness, under a landslide of tools and gear, the water rising up the companionway and the roar of the waves probably very muted through the hull. If the water takes long enough, they might attempt to escape on a lungful of air- down the companionway, along the hall, through the aft door and out from under the boat – but they don’t make it. It’s too far, they die trying. Or the water comes up so hard and fast that they can’t even think. They’re up to their waists and then their chests and then their chins and then there’s no air at all. Just what’s in their lungs, a minute’s worth or so.”

I think that what makes Junger’s recreation so plausible and acceptable is that he presents options, while still writing with definitive language. I think the book is honest, and raw and that is what makes it work. You can also tell that Junger really did his homework and talked to so many people and read so much about what it is like to be on a boat that he is able to explain the different scenarios. The fact that the scenarios all end up with the same outcome also adds an element of strength to Junger’s recreations. He states it so plainly that it gave me chills, “Tyne, Pierre, Sullivan, Moran, Murphy, and Shatford are dead.”

I recommend The Perfect Storm to anyone. The technical aspects of boat design and mechanics coupled with weather patterns and the physics of how together they affect a boat at sea are so well interspersed with narrative that the story holds your attention the entire way through. I thought the book was easy to get into and handle, while still being able to draw you back over and over if you need to put it down or are reading while traveling. I felt like I learned the basics about fishing, boats, weather, rescue protocol, the physics of the ocean, and the social side of fishing life. There is so much information it opens up a different world for readers, which I think makes it really worth your time.

It is also worth noting that The Perfect Storm was made into a film in 2000 starring George Clooney as Billy Tyne and Mark Wahlburg as Bobby Shatford. I haven’t seen it, and thus have no recommendation to give but from the trailer it looks like some cinematic liberties were taken with the story while still making an interesting film. I’ll be putting it on my ever-growing list of things to see when I have more time.

How Endangered Is Endangered Enough?

Do you care that a rare type of freshwater mussel has been nearly wiped out? Unless you are like me in the throes of Summer and I am still looking-for-a-job-limbo, I doubt you have the time to give more than a moment of attention to the freshwater pearl mussels in Cumbria in the United Kingdom…if that. In my daily perusing of the BBC I saw this article, Rare mussels ‘almost’ wiped out and I couldn’t help but think A) how in danger is in danger enough to warrant media coverage and B) does covering close calls for endangered species result in ‘boy who cried wolf’ response from the public?

In summary, the article is about a massive die-off of freshwater peal mussels (Margaritifera margaritifera) which are a type of mollusk. The BBC reported that 80,000 of the mussels were lost in a single event out of a total estimated population of 12 million in England and Scotland. It was speculated that the event was caused by a loss of outflow from a lake that caused water temperature to go up and oxygen levels to go down. According to the BBC’s article the loss is significant because it happened in an individual incident and because the freshwater pearl mussel is listed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as one what the BBC called the most endangered species.

In summary, the article is about a massive die-off of freshwater peal mussels (Margaritifera margaritifera) which are a type of mollusk. The BBC reported that 80,000 of the mussels were lost in a single event out of a total estimated population of 12 million in England and Scotland. It was speculated that the event was caused by a loss of outflow from a lake that caused water temperature to go up and oxygen levels to go down. According to the BBC’s article the loss is significant because it happened in an individual incident and because the freshwater pearl mussel is listed by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) as one what the BBC called the most endangered species.- Extinct

- Extinct in the Wild

- Critically Endangered

- Endangered

- Vulnerable

- Near Threatened

- Least Concern

- Data Deficient

- Not Evaluated