I don’t actually hate children, there is a story attached to this title. Please don’t send me angry emails. Also, since I’m about to rant about charitable giving for full disclosure you should know I work for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. There will also be sarcasm, so read accordingly.

A few weeks ago I was checking out at a national grocery store chain that shall remain nameless. I had stopped in after work and was rooting through my giant bag for my wallet when I got asked the standard “would you like to donated $1 to fill in the blank” in this case it was “healthy school lunches.” My answer, as I was swiping my card, was “no thank you.” Not because I don’t think children should have access to healthy meals through their schools, but because I had no idea what this charity was. Sure, I could have peppered the woman at the check out with questions about which organization the money was going to benefit, what schools did it work in, what kind of food were we talking about, but if I demanded calorie counts would she have known? On top of that I, and I’m sure everyone behind me in line, had somewhere to be. I was in a rush. I donate to other things. If I gave my obligatory $1 every time I got asked, I’d be giving away money every day. I had reasons for saying no so I expected that to be the end of the exchange.

It was of course not the end of the exchange. As I was swiping my card, the woman at the register responded to my “no thank you” with “why, you hate kids?” Yes. Obviously. That’s it. Little bastards needing all that nurturing and attention. It’s not like they’re the future of America or anything, they definitely don’t deserve healthy lunches. Let’s just give everyone the physical and emotional burdens of obesity! Nothing like a little diabetes to set the kids straight. Come, on! Just because I don’t want to fork over my $1 for an unknown charity doesn’t make me a child hating monster. I don’t work with kids regularly, but I’ve made it my mission this year to write a blog post every month introducing first graders in my hometown to different scientists that I’ve met on Twitter. I care about education, and yes I care about issues like obesity and access to healthy food.

In retrospect, I should have done more than just fix the woman working the register with my best dirty look, but I didn’t. Upon seeing my reaction she quickly covered with “just kidding” which for me just amounted to, “please don’t ask to speak to my manager.”As I said, I was in a rush so while still pretty ticked I just grabbed my bag and walked out of the store but this whole incident bugged me. I’m blogging about it weeks later, so clearly it has lingered.

In retrospect, I should have done more than just fix the woman working the register with my best dirty look, but I didn’t. Upon seeing my reaction she quickly covered with “just kidding” which for me just amounted to, “please don’t ask to speak to my manager.”As I said, I was in a rush so while still pretty ticked I just grabbed my bag and walked out of the store but this whole incident bugged me. I’m blogging about it weeks later, so clearly it has lingered.

It wasn’t just that I thought the women was rude. Or the insinuation that because I won’t give to that specific cause, I hate children. It has much more to do with how we give to charities as a whole. The give $1 to support fill in the blank model works. It works very well. Just look at places like St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital who raise millions every year doing just that. But St. Jude’s is recognizable, I’m more inclined to say yes to them because I at least have some idea that they are legitimate. But a completely unknown charity, no thank you. So why was the response to my “no” public shaming? When did we become a culture where taking the extra 30 seconds to think through the request to give was cause to embarrass me at the register?

Coming through the months of October and November, marked for breast cancer and prostate cancer awareness respectively, I think we can all identify with feeling a little bombarded by pleas to donate. But donate to what exactly? Buy a cookie, buy a bracelet, buy a pair of windshield wipers. Particularly with breast cancer awareness month, everything turns pink, and we are supposed to believe that our consumption of these products is helping cancer patients. But is it? I saw many examples of the ways that all of this product consumption doesn’t help the people you intend it to chronicled on twitter – especially with the hashtag #pinknausea started by Xeni Jardin of Boing Boing. Why aren’t we more careful with our money when it comes to supporting causes? There are any number of cancer charities or research organizations you could donate to when October or November roll around. But we keep buying the cookies and the bracelets, despite warnings to “Think Before You Pink.”

Is the worst that we are doing just spreading apathy toward doing our duty to ensure that our money goes to a responsible place where it will have an impact? Is “slacktivism” relatively harmless? I’ll answer my own question here with no, it’s not. When you support an awareness campaign, don’t you wonder what their action is going to be? What is the increased awareness actually going to do?

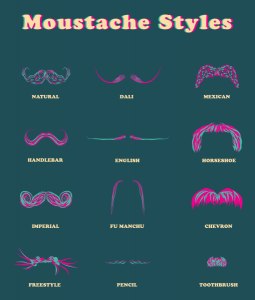

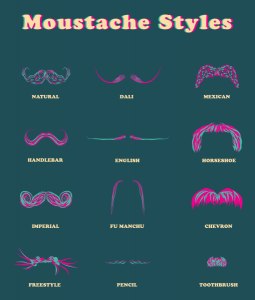

This brings me to the moustaches. You may have spotted many of your male friends or relatives sporting a little excess facial hair this month, I certainly have. It is November, also known at Movember a month dedicated to moustaches…and prostate cancer. Although what moustaches and prostates have to do with one another I’m not sure exactly, I suppose it is the association with manliness. Regardless, the Movember campaign encourages men to grow a moustache for a month to help raise awareness, and funds, for prostate cancer. Now I admire moustaches as much as the next gal, although sometimes things just go too far (oh, the things that can’t be unseen!) but really are the men out there growing and grooming their facial hair doing anything for prostate cancer?

This brings me to the moustaches. You may have spotted many of your male friends or relatives sporting a little excess facial hair this month, I certainly have. It is November, also known at Movember a month dedicated to moustaches…and prostate cancer. Although what moustaches and prostates have to do with one another I’m not sure exactly, I suppose it is the association with manliness. Regardless, the Movember campaign encourages men to grow a moustache for a month to help raise awareness, and funds, for prostate cancer. Now I admire moustaches as much as the next gal, although sometimes things just go too far (oh, the things that can’t be unseen!) but really are the men out there growing and grooming their facial hair doing anything for prostate cancer?

The issues associated with Movember and prostate cancer screening are summarized really well in this post by Gary Schwitzer on HealthNewsReview.org (and reading it is what really motivated me to write this!) Essentially, when it comes to prostate cancer sometimes routine screening can lead to unnecessary treatments and procedures that can do some harm. There are also benefits to screening. In general when it comes to screening the answer is to talk it through with your doctor and figure out what is right for you. Still, these are not clear cut issues and even doctors have different opinions. The New England Journal of Medicine featured prostate cancer screening in their Clinical Decisions column which pits opposing medical views against each other and asked readers to vote on them (see here and here, though I’m not sure about your access situation.) The results came back in favor of screening with the prostate cancer specific antigen (PSA) test. But, it wasn’t a landslide.

I’ve known that my friends grew moustaches in November for at least two years. I’ve known that this had something to do with prostate cancer for about three weeks. Shame on me I guess, but clearly this is a problem for an awareness campaign, and it isn’t the only one. While some people are out there growing moustaches just for the awesomeness, for people who do take Movember seriously when we say we want to raise awareness of prostate cancer, what are we advocating for? More screening? Prostate cancer screening, like most screening, is a giant kettle of worms.

So does that mean we shouldn’t give to Movember when our moustached brethren ask us? No, if you want to support the Prostate Cancer Foundation or LiveStrong, then you should. But you should at least know that those are the organizations that Movember supports. We need to think more critically about these awareness campaigns, and what we are doing when we agree to give $1 to any charity that asks. All of this – my grocery store I don’t hate children episode, the pinking of America, and all the moustache growing – all come together with one main point. It isn’t enough to just participate or toss in your $1. You need to know and understand what you are giving to and why. Supporting cancer research is so important, especially in these days when funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute is so hard to come by. All the more reason why if you are going to give, you should give intelligently. Make sure it matters.

I said at the beginning of this post that I work for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. This little fact makes me undoubtedly biased when it comes to charitable giving, so I’m not going to give you any recommendations about where to give. Your money is yours, and you should make those decisions yourself. That’s what I do. But, since I’ve spent this whole post ranting about giving smarter I am going to recommend that should you find yourself interested in giving to cancer research or healthy lunches or veterans or anything else you check out where your money is going. Charity Navigator is one tool that I really like to help sort through which organizations handle their money well and might help you figure out where you can do some real good.

In the meantime I’ll just be over here ranting, admiring moustaches, and hating children.

Anne-Marike: I studied Psychology in Bochum in Germany and Neuropsychology in Masstricht in the Netherlands. I also did some work in a lab in Dunedin in New Zealand. After that I did my PhD in Neuroscience in Cologne in Germany. Erin: What type of scientist are you?

Anne-Marike: I studied Psychology in Bochum in Germany and Neuropsychology in Masstricht in the Netherlands. I also did some work in a lab in Dunedin in New Zealand. After that I did my PhD in Neuroscience in Cologne in Germany. Erin: What type of scientist are you?