I grew up believing that there were nine planets: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune and Pluto. Then, in 2006 my understanding of the universe was shaken when poor little Pluto was stripped of its classification and labelled just another object in the Kuiper Belt, an area that extends from the orbit of Neptune and contains thousands of icy “objects” with the same consistency as Pluto.

The decision that Pluto was not a planet came in 2006 based on the 2005 discovery of Eris, an object larger than Pluto, in the Kuiper Belt. Pluto and Eris are both considered “dwarf planets.” According to the International Astronomical Union for an object to be a planet it must meet three criteria:

- It needs to orbit around the sun (or if part of a different solar system than ours, it needs to orbit around another star)

- It needs to have enough gravity to pull itself into a spherical shape

- It must be the dominant gravitational body in its orbit (thus any smaller body in its orbit is either consumed or flung away by the object’s gravitational pull – being smaller than Eris, Pluto clearly doesn’t qualify)

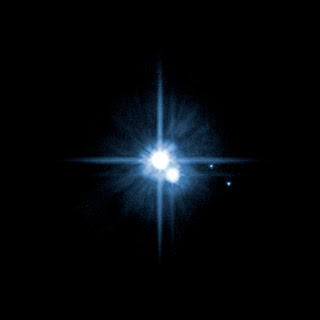

|

| Pluto by the Hubble Space Telescope via Wikimedia Commons |

But why digress on a five-year old story about a former planet’s rejection? Well, because the issue of what makes something a planet seems like it could again be coming into question. This week the BBC ran the article “Free-floating planets found with no star in sight” talking about the new discovery of objects in space that are seemingly un-connected to a star. The BBC article is referencing the research “Bound and unbound planets abound” featured in Nature, and as we learned from the Pluto experience, criteria #1 for being classified as a planet is that the object in question needs to orbit a star.

So then what is going on with the new discovery of at least 10 objects the size of Jupiter that don’t orbit a star? The research suggests that objects like this might be so common, they actually outnumber stars 2:1. While the BBC’s article states that researcher are cautious to completely flip our understanding of the universe based on a single study – if true, it would completely flip our understanding of the universe.

The definition of a planet is firmly grounded in the three criteria listed above, so these new objects don’t fit the bill because #1 – orbiting a star is violated. But then, what are they? The answer to that is a little complicated. The BBC’s article doesn’t explain it. So, since I have zero background in astronomy, I did some digging and found Phil Plait’s blog Bad Astronomy for Discover.

According to Plait’s post called “The galaxy may swarm with billions of wandering planets,” the objects talked about in the Nature study either formed like stars or they formed like planets in solar systems (like our own) and got tossed out. Plait favors the latter, saying they are most likely rejects from other solar systems.

He explains that massive planets often form along the outside of a solar system, and then migrate inward toward the center star. This could cause other plants in the path of the migrating planet to undergo changes in their orbit, or even get flung out the solar system completely. It is these planets that get flung out of their solar system by the movement of larger planets that could be the star-less objects featured in the Nature study. The evidence in favor of this theory is the prevalence of large plants that orbit very close to their stars.

So most likely – the objects in question ARE planets, they formed like planets, in a solar system that orbited a star. But, somewhere along the way they got tossed out of their solar system, and thus became free-floating planets.

I’ll be interested to see if there is any kind of distinction as far as name or classification that these rogue planets are given, that identifies that they are different than your typical planet. Lord knows losing Pluto was bad enough, I’m not sure what I’ll do if there is another planetary shake up. Its rough seeing things you learned when you were six get turned on their head. But, it is also incredibly cool how much new information the universe still has to give up. I really love the idea that there could be so many free-floating planets out there waiting to be discovered.