When I was six my parents, brother and I moved to a cute brick house just the rights size for us. It hadn’t been lived in for a few years because the elderly couple that had owned it passed away in hospice, while a caretaker maintained the house. When my parents bought it, the house was a blast from the past. Pale yellow bathroom fixtures, peeling linoleum floors, blue eagle kitchen wallpaper, mustard yellow velour couch, seafoam green paint in the living room. Because the home’s previous owners had passed away, some strange/awesome/old features (like that couch) got tossed in with the sale.

Moving meant that for the first time in our lives my brother (slightly older) and I would each get our own room. My room was going to be pink, and it was going to be Aladdin and Jasmine themed and I was thrilled. That is – I was thrilled until the kids down the street told me the “truth” my parents were hiding. The house, specifically MY room, was haunted.

Obviously, the house was haunted. Old people lived there, and they DIED. Of course they came back to haunt the house. Specifically, I was told, they haunted my closet. The proof of this haunting was the fact that sticks and leaves stuffed in the mail slot of the house while it was unoccupied waiting for sale MYSTERIOUSLY disappeared. No one lived there, so then who moved them, right? Clearly the answer was ghosts, and what ghost wouldn’t like being trapped in a closet?

At the wise old age of six I was skeptical, but didn’t understand enough about real estate to know that prior to showing a house any real estate agent would remove random detritus shoved through the mail slot by pesky neighborhood kids. When I reported my news of the haunting to my Mom she informed me that there was no such thing as ghosts. But then why did I always check to make sure the closet was shut firmly before going to bed? Why did I RUN up the basement stairs every time I had to go down there? Why did the old furniture and fixtures seem like the perfect backdrop for a ghost story?

I’ve now lived in that house for over 15 years, and I’ve never had a close encounter of the ghostly kind. But the ghost story told to me back then about my haunted closet is to my memory my first real encounter with the supernatural. Flash forward to my college years, and my interest in ghost stories was again peaked by the Discovery Channel show A Haunting. My roommate and I started watching A Haunting every weekday because it was on at 3pm, when we didn’t have class. We quickly became enthralled, coming to such conclusions as “it always happens to the Catholics” and “blessing your new home is asking for it.”

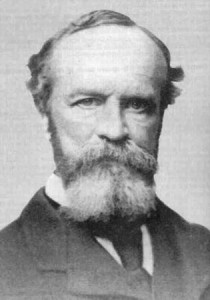

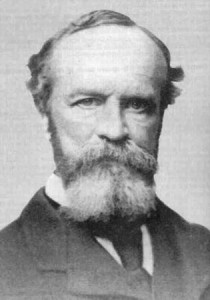

I’ve never felt any otherwordly connection to spirits or the like, but I find it hard to dismiss the possibility of life after death all together. Just because there is no proof, or at least no definitive proof, doesn’t mean hinky things don’t happen, right? So with this background and frame of mind, I was all too excited to read “Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death” by Deborah Blum.

Those who read my blog regularly know that I’m studying at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and I have Deb Blum as a professor. No, she doesn’t require or even ask us to read her books. Yes, I’ve already gotten my grades for the semester, and no, I’m not sucking up by reading through her books. I’m curious about the work of the person I’m learning from. I’ve given my thoughts on Poisoner’s Handbook, and Love At Goon Park & The Monkey Wars in previous posts – and just want to share a few reflections from Ghost Hunters.

Those who read my blog regularly know that I’m studying at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and I have Deb Blum as a professor. No, she doesn’t require or even ask us to read her books. Yes, I’ve already gotten my grades for the semester, and no, I’m not sucking up by reading through her books. I’m curious about the work of the person I’m learning from. I’ve given my thoughts on Poisoner’s Handbook, and Love At Goon Park & The Monkey Wars in previous posts – and just want to share a few reflections from Ghost Hunters.

The book chronicles the rise of the American and British Societies for Psychical Research, through several characters, most dominantly Edmund Gurney, Henry Sidgwick, Frederic Myers, Richard Hodgson, and William James (brother of the writer Henry James – The Aspern Papers, the Turn of the Screw, etc.) and of course the famous medium Leonora Piper. These people set out in the 1880’s to try to prove the existence of life after death. Obviously, since this is something that has yet to be determined 130 years later, they did not succeed. But what they did do was devote their lives to trying to make psychical research a legitimate science.

The researchers studied phenomenon like slate writing, floating furniture, the appearance of specters (white floating blobs, etc.) strange lights, blowing curtains, and the claims by mediums that they could speak to the dearly departed. The majority of what the researchers did was expose fraud. But there was one medium, that the majority of psychical researchers believed in – Mrs. Piper. This medium stood out for the fact that she didn’t charge for sittings, and wasn’t making money off of her “abilities.” One of the most interesting experiments with the medium described in Blum’s book is the “cross-correspondence” study.

The term telepathy was developed by the first psychical researchers to describe the ability to communicate thoughts mentally. They set up an experiment to see if the spirits of people who had died would be able to take a thought conveyed by a medium, and transmit it to a different medium. Mrs. Piper was sent to London, the medium Margaret Verrall was in Cambridge, and Alice Kipling Fleming (sister of Rudyard Kipling) was in India. Myers, Gurney, and Hodgson were by this time deceased, so the remaining psychical researchers set out to communicate with their old colleagues.

Lines of poems and words in Greek and Latin (languages unknown to the mediums) were reportedly conveyed between the mediums in their different locations. But is that evidence of life after death, or telepathy, or spiritual communication? I don’t know. At the time (in the early 1900’s) it wasn’t enough proof. The argument was that the psychical researchers wanted so badly to prove that they could communicate with their departed colleagues and show that the mediums were real, that their desires colored the study and skewed results. Perhaps making something out of nothing. Perhaps so dedicated and well-intentioned that they did summon up spiritual communication.

What I like most about Ghost Hunters is that Blum never decides whether any of the experiments did or did not prove the existence of life after death. I don’t see how she could. I think that even today, while there are so many “events” that can’t be explained away as tricks, smoke and mirrors, or active imaginations, there is still nothing definitive to show that spirits exist. I don’t think there ever will be. I think that this is a case where, “for those who believe no proof is necessary, for those who don’t believe no proof is possible” (Stuart Chase.)

While I am a firm believer that nothing haunts my closet, I can’t explain “the unexplained” and I won’t try. But thats not what Ghost Hunters is about anyway. It is a fascinating history of the work of several researchers (and friends) trying to make sense of the things that go bump in the night using the scientific experimental standards they believed in most. Ultimately I think it comes down to the belief that eventually science can explain everything – and having to accept that it hasn’t, and maybe never will.

For me, the drama in the book is not will the psychical experiments be successful but rather, will they ever be accepted? Ghost Hunters tackles the issue of exclusivity in the scientific community and examines where scientists draw their line in the sand as far as what should and should not count as science. The definition of science is the intellectual and practical activity encompassing the systematic study of the structure and behavior of the physical and natural world. Do ghost hunters count? Should they count? Who gets to decide what is science and what is a waste of time?

Of the books that I have read by Blum, I enjoyed Ghost Hunters the most. I love science, but sometimes even the best science books can get confusing and having to work to maintain clarity, I lose interest. The sign of a great writer is to be able to take a subject and weave together the stories of all the different people involved in developing that subject, without getting the reader lost. I was never confused while reading Ghost Hunters about who was who or what was going on. I was enthralled from start to finish – not because I love a good ghost story, but because I love the richness of science history, and the real stories of these rogue researchers.