On why the Onion deserves a Pulitzer Prize:

All posts by erin

Blogging Is A Battle And We Are The Soldiers

A Geek Roundup: The Best Science Posts From My Internship

I know I haven’t been posting on here as often as I used to, but that doesn’t mean that I’ve been slacking. My summer internship is working as a blogger for Geekosystem, one of the Abrams Media Network websites. I’ve been writing posts about a lot of interesting science over at Geekosystem, and I wanted to highlight some of my favorites from the past month.

|

| Exposure to puppy pictures are just one perk of being a Geekosystem Intern |

Just a small sampling of the very cool science that has been going on in the last month. There are so many interesting things that I’ve gotten to cover for Geekosystem (though I tend to pitch all science stories and must settle on about half, they still let me cover a lot of great stuff). I’ve been learning a lot about how to tell if something you see on the internet is legitimate, what sources to go to for post ideas, and how to write for a varied audience that doesn’t always know they’re going to be interested in a science topic.

One thing I’ve been struggling with while writing for Geekosystem are the comments I get on my posts. Some of them are nice and either point out a typo or minor error or just provide an opinion about the post, but the majority I either don’t understand what the criticism is or I’m being accused of making mistakes that I don’t think I have. I’m being encouraged to interact more with people in the comments, but I’m not sure how to handle it really. Although knowing the internet, I know that comments could be much much worse, and are for many people. I just need to get a thicker skin I suppose.

I’ll try to do more roundups of the science posts I write for Geekosystem, but never fear I have no plans to abandon my own little corner of the internet here, where I can say what I want and the commenters are people I know!

New Method May Provide Clues To Dinosaur Body Temperature

Scientists have many questions about how the internal condition of dinosaurs (not preserved in fossilized remains) may have influenced the way those creatures lived. One of the conditions in question is whether or not dinosaurs were cold blooded or warm blooded and what were their internal temperatures. But now a team of researchers from the California Institute of Technology believe they have developed a method by which they can identify the internal temperature of dinosaurs based on fossilized teeth.

|

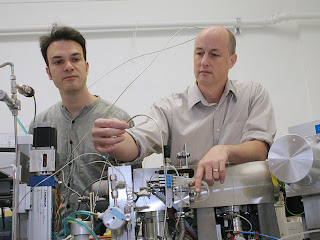

| Caltech Geochemists Rob Eagle (L) and John Eiler |

The researchers, led by postdoctoral researcher Robert Eagle, studied isotopic concentrations in 11 fossilized teeth from sauropods (the long-tailed, long-necked dinosaurs). The teeth were recovered from sites in Tanzania, Wyoming and Oklahoma and belonged to Brachiosaurus and Camarasaurus dinosaurs.

The method used for this analysis is called a clumped isotope technique. The concentrations of the isotopes carbon-13 and oxygen-18 in bioapatite, a mineral found in teeth and bone. How often these isotopes bond with each other (clump, if you will) hinges on the temperature. The lower the temperature the more the isotopes tend to bond with each other. So, the researchers measured how these isotopes clumped together to determine the environmental (in this instance the internal condition of the dinosaur) temperature. At least, the temperature of the tooth.

The study allowed the researchers to estimate the temperature of Brachiosaurus to 100.8 degrees Fahrenheit and the temperature of Camarasaurus to 96.3 degrees Fahrenheit. This is warmer than living and extinct reptile species (like crocodiles) but is cooler than birds both of which are believed to be modern descendants of the dinosaurs. According to the researchers the measurements are accurate to within one or two degrees.

|

| Drilling a Camarasaurus tooth |

Prior to this research, the best way to evaluate the internal temperature of dinosaurs was to infer what would be most likely based on the dinosaur’s behavior and physiology. However, researchers sought a method that would be more specific. That’s not to say the researcher’s new method is infallible. While they have made big claims about it being “bullet proof,” it remains to be seen whether this method is the most accurate and effective.

The study led the Caltech researchers to conclude that dinosaurs were warm blooded (have an internal mechanism to moderate body temperature), but they warn that the issue is actually more complicated that just temperature readings. Even if the creatures were cold blooded and relied on their environment for warmth, they still could have had very warm bodies. Unfortunately knowing the temperature of the teeth don’t answer all of the remaining questions about dinosaur temperature.

The scientists hope to expand upon this study to include analysis of the teeth of other species of extinct vertebrates, in addition to determining the internal temperatures of small and young dinosaurs that may reveal more about how temperature affected the way these creatures lived. The research paper was published in ScienceExpress. More information (from a press release) is available from Caltech and in the following video (which were both used as sources for this post.)

The Arabian Oryx’s Comeback Story

|

| Arabian Oryx, via Wikimedia Commons |

Under IUCN Red List Guidelines a species can only move to a lower category if none of the criteria for the higher category have been met for five years or more. To be considered endangered there must be 250 or fewer mature individuals of a species, so the Arabian oryx, which is doing well at over 1000, will be listed as Vulnerable starting this year.

Under IUCN Red List Guidelines a species can only move to a lower category if none of the criteria for the higher category have been met for five years or more. To be considered endangered there must be 250 or fewer mature individuals of a species, so the Arabian oryx, which is doing well at over 1000, will be listed as Vulnerable starting this year. Interestingly, the population that was re-introduced to Oman (where the last wild Arabian oryx were killed before it went extinct in the wild) has been struggling. The Oman population was hurt through illegal live capture for private sale, and has been rendered ineffective because only males remain. Most new populations are in secure areas that are relatively safe from poaching, but animals that wander outside protected sites have no guarantee of safety. Future release locations for animals bred through captivity will be determined by the potential effects of drought and overgrazing, which have reduced available areas where populations could thrive.