Last semester I read many more books (thus I did a lot more book reviews) than this semester which has mostly been devoted to academic research papers. But I do have two books that need reading for my zoology class on human and animal behavior with Patricia McConnell.

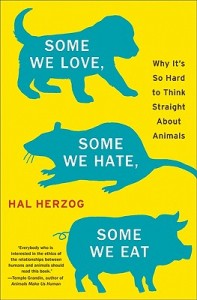

I finally finished the first of the two assigned books, Hal Herzog’s Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat – Why It’s So Hard to Think Straight About Animals. I’ve been reading Herzog’s book all semester, so my evaluation of it draws on a slightly disjointed memory but I think I can summarize his main point with two statements:

I finally finished the first of the two assigned books, Hal Herzog’s Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat – Why It’s So Hard to Think Straight About Animals. I’ve been reading Herzog’s book all semester, so my evaluation of it draws on a slightly disjointed memory but I think I can summarize his main point with two statements:

1. Most people choose not to (or don’t know enough to) think about their personal moral philosophy. Not thinking about how we feel about animals is what allows us to love puppies so much while we happily chow down on a Big Mac.

2. Those people who have spent a tremendous amount of time trying to discern their personal moral philosophy about animals either A. remain horribly conflicted or B. Choose a philosophy with regards to the treatment of animals that societal pressures make very difficult to implement (for example, all creatures are equal – if you save an iguana from a burning building instead of a human baby, society is not going to look kindly upon you regardless of your belief that the iguana and the baby are equals)

Herzog’s answer to his main question “why is it so hard to think straight about animals?” largely comes down to because you’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t.

The book tries hard to cover a variety of topics that impact the way we feel about animals, some obvious (factory farming, animals in research, hunting) and some less so (cockfights, dog shows, gender roles.) I don’t intend to go into his arguments for and against certain behaviors, but to give an example of the kind of analysis he provides I will share the anecdote from his chapter “The moral status of mice,” on the use of animals for biological research.

Herzog frames animal research this way: Think of Steven Spielberg’s 1982 classic film ET. Remember how close Elliott and ET became, and how heart wrenching it was to see ET go back to his home planet? Well, what if there was a disease destroying the alien’s on ET’s home planet, and the reason he really came to earth was to scout out organisms of lesser intelligence to test possible remedies on. Elliott’s intelligence was far less than ET’s. So how would you feel if at the end of the movie, ET kidnapped Elliott and took him back to his home planet to live the rest of his life as the subject of research. It would save millions of aliens. But ET still essentially destroys Elliott’s life. Not really a satisfactory ending, I’d say.

So if we don’t want ET to kidnap Elliot just because he is of lesser intelligence, then what do we do when humans are like ET and mice are like Elliot? Should we experiment on mice just because they are of lesser intelligence? Previous logic would lead us to say no, we should not experiment on the mice. But yet, I’m still in favor of animal research. Philosophically, I shouldn’t be. But there is something about experimenting on a member of my own species that I find morally reprehensible. It is the reason we don’t conduct experiments on people in coma’s or with mental retardation. But if you are always putting humans first, how can you still treat animals with respect and moral standing?

I’m not here to answer the questions thinking critically about animals pose. Herzog has 280 pages of highly intelligent, moving, and entertaining explanation, and he still doesn’t answer most of them. But he will get you thinking about your own behavior, why some animals matter to us more than others, and why humans think the way we do.

It is important for everyone: meat eaters, vegetarians, pet lovers, people who avoid animals, etc. to think about why they feel the way they do about animals. I was surprised by the conflicts in my own way of thinking, and sadly I now fall into column A – thinking critically, but still horribly confused. At least I’m thinking right?