On July 17, Sciobeantown headed over to the Broad Institute in Cambridge, MA to join in on their four week lecture series: Midsummer Nights’ Science. Members of Sciobeantown took to Twitter with the hashtags #broadtalks and #sciobeantown to livetweet the event, which featured a talk from cancer genomics researcher Levi Garraway.*

On July 17, Sciobeantown headed over to the Broad Institute in Cambridge, MA to join in on their four week lecture series: Midsummer Nights’ Science. Members of Sciobeantown took to Twitter with the hashtags #broadtalks and #sciobeantown to livetweet the event, which featured a talk from cancer genomics researcher Levi Garraway.*

If you missed the event, a video of the talk called, “Exploring the genome’s dark matter** what frontiers of genomic research are revealing about cancer” is now online. You can also check out Sciobeantown’s contribution to the Twitter discussion with this Storify of the event by Amanda Dykstra. Thank you to the Broad Institute for setting aside space at this event (which filled the room to capacity) so that Sciobeantown could participate!

*Dr. Garraway is a researcher at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, in addition to his work at the Broad Institute and Harvard Medical School. I do cover his melanoma work as part of my job at Dana-Farber.

**Using dark matter as a metaphor for the non-protein coding portion of the genome has been the subject of some science writer snark (possibly from me…okay, from me) but the title of the talk is the title of the talk, folks.

Category: Cancer

On Admiring Moustaches and Hating Children

I don’t actually hate children, there is a story attached to this title. Please don’t send me angry emails. Also, since I’m about to rant about charitable giving for full disclosure you should know I work for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. There will also be sarcasm, so read accordingly.

A few weeks ago I was checking out at a national grocery store chain that shall remain nameless. I had stopped in after work and was rooting through my giant bag for my wallet when I got asked the standard “would you like to donated $1 to fill in the blank” in this case it was “healthy school lunches.” My answer, as I was swiping my card, was “no thank you.” Not because I don’t think children should have access to healthy meals through their schools, but because I had no idea what this charity was. Sure, I could have peppered the woman at the check out with questions about which organization the money was going to benefit, what schools did it work in, what kind of food were we talking about, but if I demanded calorie counts would she have known? On top of that I, and I’m sure everyone behind me in line, had somewhere to be. I was in a rush. I donate to other things. If I gave my obligatory $1 every time I got asked, I’d be giving away money every day. I had reasons for saying no so I expected that to be the end of the exchange.

It was of course not the end of the exchange. As I was swiping my card, the woman at the register responded to my “no thank you” with “why, you hate kids?” Yes. Obviously. That’s it. Little bastards needing all that nurturing and attention. It’s not like they’re the future of America or anything, they definitely don’t deserve healthy lunches. Let’s just give everyone the physical and emotional burdens of obesity! Nothing like a little diabetes to set the kids straight. Come, on! Just because I don’t want to fork over my $1 for an unknown charity doesn’t make me a child hating monster. I don’t work with kids regularly, but I’ve made it my mission this year to write a blog post every month introducing first graders in my hometown to different scientists that I’ve met on Twitter. I care about education, and yes I care about issues like obesity and access to healthy food.

In retrospect, I should have done more than just fix the woman working the register with my best dirty look, but I didn’t. Upon seeing my reaction she quickly covered with “just kidding” which for me just amounted to, “please don’t ask to speak to my manager.”As I said, I was in a rush so while still pretty ticked I just grabbed my bag and walked out of the store but this whole incident bugged me. I’m blogging about it weeks later, so clearly it has lingered.

In retrospect, I should have done more than just fix the woman working the register with my best dirty look, but I didn’t. Upon seeing my reaction she quickly covered with “just kidding” which for me just amounted to, “please don’t ask to speak to my manager.”As I said, I was in a rush so while still pretty ticked I just grabbed my bag and walked out of the store but this whole incident bugged me. I’m blogging about it weeks later, so clearly it has lingered.

It wasn’t just that I thought the women was rude. Or the insinuation that because I won’t give to that specific cause, I hate children. It has much more to do with how we give to charities as a whole. The give $1 to support fill in the blank model works. It works very well. Just look at places like St. Jude’s Children’s Research Hospital who raise millions every year doing just that. But St. Jude’s is recognizable, I’m more inclined to say yes to them because I at least have some idea that they are legitimate. But a completely unknown charity, no thank you. So why was the response to my “no” public shaming? When did we become a culture where taking the extra 30 seconds to think through the request to give was cause to embarrass me at the register?

Coming through the months of October and November, marked for breast cancer and prostate cancer awareness respectively, I think we can all identify with feeling a little bombarded by pleas to donate. But donate to what exactly? Buy a cookie, buy a bracelet, buy a pair of windshield wipers. Particularly with breast cancer awareness month, everything turns pink, and we are supposed to believe that our consumption of these products is helping cancer patients. But is it? I saw many examples of the ways that all of this product consumption doesn’t help the people you intend it to chronicled on twitter – especially with the hashtag #pinknausea started by Xeni Jardin of Boing Boing. Why aren’t we more careful with our money when it comes to supporting causes? There are any number of cancer charities or research organizations you could donate to when October or November roll around. But we keep buying the cookies and the bracelets, despite warnings to “Think Before You Pink.”

Is the worst that we are doing just spreading apathy toward doing our duty to ensure that our money goes to a responsible place where it will have an impact? Is “slacktivism” relatively harmless? I’ll answer my own question here with no, it’s not. When you support an awareness campaign, don’t you wonder what their action is going to be? What is the increased awareness actually going to do?

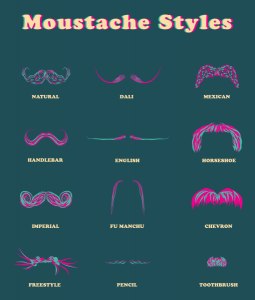

This brings me to the moustaches. You may have spotted many of your male friends or relatives sporting a little excess facial hair this month, I certainly have. It is November, also known at Movember a month dedicated to moustaches…and prostate cancer. Although what moustaches and prostates have to do with one another I’m not sure exactly, I suppose it is the association with manliness. Regardless, the Movember campaign encourages men to grow a moustache for a month to help raise awareness, and funds, for prostate cancer. Now I admire moustaches as much as the next gal, although sometimes things just go too far (oh, the things that can’t be unseen!) but really are the men out there growing and grooming their facial hair doing anything for prostate cancer?

This brings me to the moustaches. You may have spotted many of your male friends or relatives sporting a little excess facial hair this month, I certainly have. It is November, also known at Movember a month dedicated to moustaches…and prostate cancer. Although what moustaches and prostates have to do with one another I’m not sure exactly, I suppose it is the association with manliness. Regardless, the Movember campaign encourages men to grow a moustache for a month to help raise awareness, and funds, for prostate cancer. Now I admire moustaches as much as the next gal, although sometimes things just go too far (oh, the things that can’t be unseen!) but really are the men out there growing and grooming their facial hair doing anything for prostate cancer?

The issues associated with Movember and prostate cancer screening are summarized really well in this post by Gary Schwitzer on HealthNewsReview.org (and reading it is what really motivated me to write this!) Essentially, when it comes to prostate cancer sometimes routine screening can lead to unnecessary treatments and procedures that can do some harm. There are also benefits to screening. In general when it comes to screening the answer is to talk it through with your doctor and figure out what is right for you. Still, these are not clear cut issues and even doctors have different opinions. The New England Journal of Medicine featured prostate cancer screening in their Clinical Decisions column which pits opposing medical views against each other and asked readers to vote on them (see here and here, though I’m not sure about your access situation.) The results came back in favor of screening with the prostate cancer specific antigen (PSA) test. But, it wasn’t a landslide.

I’ve known that my friends grew moustaches in November for at least two years. I’ve known that this had something to do with prostate cancer for about three weeks. Shame on me I guess, but clearly this is a problem for an awareness campaign, and it isn’t the only one. While some people are out there growing moustaches just for the awesomeness, for people who do take Movember seriously when we say we want to raise awareness of prostate cancer, what are we advocating for? More screening? Prostate cancer screening, like most screening, is a giant kettle of worms.

So does that mean we shouldn’t give to Movember when our moustached brethren ask us? No, if you want to support the Prostate Cancer Foundation or LiveStrong, then you should. But you should at least know that those are the organizations that Movember supports. We need to think more critically about these awareness campaigns, and what we are doing when we agree to give $1 to any charity that asks. All of this – my grocery store I don’t hate children episode, the pinking of America, and all the moustache growing – all come together with one main point. It isn’t enough to just participate or toss in your $1. You need to know and understand what you are giving to and why. Supporting cancer research is so important, especially in these days when funding from the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute is so hard to come by. All the more reason why if you are going to give, you should give intelligently. Make sure it matters.

I said at the beginning of this post that I work for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. This little fact makes me undoubtedly biased when it comes to charitable giving, so I’m not going to give you any recommendations about where to give. Your money is yours, and you should make those decisions yourself. That’s what I do. But, since I’ve spent this whole post ranting about giving smarter I am going to recommend that should you find yourself interested in giving to cancer research or healthy lunches or veterans or anything else you check out where your money is going. Charity Navigator is one tool that I really like to help sort through which organizations handle their money well and might help you figure out where you can do some real good.

In the meantime I’ll just be over here ranting, admiring moustaches, and hating children.

Medical History is Biography

The title of this post is a very elegant summation provided by Siddhartha Mukherjee of a talk that he gave at Harvard Medical School (HMS) last week. I was lucky enough to be at HMS (in the overflow room, sadly) to listen to Mukherjee’s talk. You may remember that I recently read and reviewed his Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. I leapt at the chance to see him talk about his work because I loved the book so much, I gave it a full recommendation for everyone with no caveats, which doesn’t happen often.

Mukherjee was the speaker for the 37th annual Joseph Garland lecture, honoring the former editor of the New England Journal of Medicine 1948-1968 and former president of the Boston Medical Library. Mukherjee is an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Columbia University, but he earned his MD from HMS and thus spent many hours in the Countway Library, which is the merged effort of HMS and the former Boston Medical Library. Mukherjee is every bit as eloquent when speaking as when writing, and I enjoyed hearing him articulate the thought process that went into his book.

The talk was called “Four Revolutions and a Funereal” and walked briefly through the history of cancer research (as much as one can in an hour) to arrive at present day. The four revolutions represented the greatest breakthroughs in the understanding of what cancer is: 1. Cancer is a disease of cells, 2. Cancer is a disease of genes, 3. Cancer is a disease of genomes, and 4. Cancer is an organismal disease. The fourth I found particularly interesting, and it is worth repeating Mukherjee’s explanation of how he defines organismal, “of or pertaining to an organism as a whole including its physiology, environment and interactions.” From everything I’ve learned in the last three months writing on a cancer biology beat, I feel like that statement certainly hits the nail on the head.

From the 1800’s when cancer was thought to be a disease caused by black bile and an imbalance of cardinal fluids, which Mukherjee jokingly called the “hydrolic theory of pathology,” our understanding of cancer has come a long way. But it seems like with every bit of progress made the field almost becomes murkier. The more we tease the problem apart, the more complicated we realize it is. From cell division, to genes that drive the process, to the proteins that control gene expression, it seems as though the smaller you go into the cell processes the more numerous the possibilities about what could go wrong get. Mukherjee closed his talk by saying that cancer is a disease of pathways, and that figuring out how to alter aberrant communication and information processing as it goes on within a cell is the future of cancer research.

Throughout the talk I was struck by the way Mukherjee managed to engage with a audience, perhaps a third of which was sitting with me in a room across the quad from where he was presenting. I was so captivated by his talk, which I thought was pretty impressive for watching a live stream. Just like in his book, he interspersed his talk with annecdotes that brought to life his personal quest for understanding which is what I think from listening to him really drove him to write the book in the first place.

An example of this is how he dedicated his book to Robert Sandler (1945-1948) a little boy who achieved a temporary remission from leukemia under Sidney Farber’s care at Boston Children’s Hospital. Though Sandler ultimately died of the disease his place in history was solidified by that landmark medical study. When Mukherjee was trying to track the identities of Farber’s early patients all he could come up with were the initials R.S. He never was able to find the identity through available records in the United States. He discovered who R.S. was while visiting his parents in India, the information was in the hands of a neighbor of theirs who was a historian and had a roster of Farber’s first chemotherapy patients. Mukherjee dedicated the book to the little boy, and after the book was published, he got a phone call from Robert Sandler’s twin brother who had seen the book in a store, opened to the dedication page and noticed his brother’s name.

This story hits at the heart of what Mukherjee meant when he said that “medical history is biography.” This holds true for science history in general. Discoveries made, research conducted, experiments performed, trials carried out – the personal narrative underscores everything. We always say that being able to craft a compelling narrative is critical to effective science communication, and this is why. People want to hear stories about other people, and science including medicine is inherently a story about people. As a speaker Mukherjee was able to do exactly what I admired so much in his book; he explained the science and told us where it was going, but he did so in a way pulled at our emotions, perceptions, and our ability to relate to other people. He made it human, driving home the idea that good writing doesn’t just serve to explain. Context is everything, and as writers our challenge is to make sense of science, to connect people with science through a context that they can understand.

If you haven’t read Emperor of All Maladies yet, you might want to get on that…

Book Review: The Emperor of all Maladies

Due to my new job as a writer at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute I now find myself writing on a cancer biology beat. I feel like there are two ways to cultivate a beat, either you can grow into a beat by developing the background knowledge and sources over time, or you can be tossed into a beat and have to do your homework very quickly to get up to speed. Obviously, taking a job at DFCI forced me to take my basic knowledge of cancer research to a higher level very quickly.

I still have a long way to go before I’ll feel comfortable with my cancer bio knowledge, but I’ve learned a lot from all of the great articles and books I’ve been reading over the last two months. One of the books I read on the recommendation of a colleague who said it really helped her when she started on this beat, was The Emperor of all Maladies: A Biography of Cancer by Siddhartha Mukherjee. A former DFCI fellow, Mukherjee is a physician, scientist, and writer. He wrote The Emperor of all Maladies in 2010, and it received a tremendous amount of acclaim including the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction.

Very rarely in a book review do I say that I think everyone should read a book. More often I recommend books with caveats that if you aren’t interested in the subject matter, don’t like nonfiction, have trouble staying focused, etc perhaps you won’t enjoy a book as much as I did. I am recommending The Emperor of all Maladies for everyone, regardless of what you normally read or are typically interested in. This book, and Mukherjee himself, deserve every ounce of praise that has been heaped upon them. There is a lot of information in The Emperor of all Maladies, and depending on how and where you read it might take you a long time to get through. It will be worth it.

Very rarely in a book review do I say that I think everyone should read a book. More often I recommend books with caveats that if you aren’t interested in the subject matter, don’t like nonfiction, have trouble staying focused, etc perhaps you won’t enjoy a book as much as I did. I am recommending The Emperor of all Maladies for everyone, regardless of what you normally read or are typically interested in. This book, and Mukherjee himself, deserve every ounce of praise that has been heaped upon them. There is a lot of information in The Emperor of all Maladies, and depending on how and where you read it might take you a long time to get through. It will be worth it.

I learned so much from this book, not just about cancer but about how to tell a long, complicated narrative in a way that is factual while still compelling. The patient narrative that the book starts and ends with brings a personal touch to the book, but the physicians, activists, and researchers interwoven into the story by Mukherjee also make this a deeply personal story. I think one of the biggest achievements of this book is being able to meld science and history to provide a foundation for the cast of characters that drive home the human impact of cancer.

The Emperor of all Maladies is masterful at doing something that so much science writing on the web and elsewhere fails to do – it provides background and context for all of the claims that it makes. Granted, developments that have advanced our knowledge of cancer biology aren’t particularly controversial, but it is still necessary to illuminate the scientific process and make clear how these discoveries come to be. This book is just solid in so many ways. The structure is great, and very effectively drives the narrative forward. The personal stories add so much to the overall understanding of cancer and its impact. The science and medical information is clear and easy to understand.

There is just so much that you can learn from this book. I don’t think I’ve come across another resource that was as interesting and entertaining while being as informative about all of the issues involved in cancer than this one. I recommend it to everyone because cancer is something that affects us all, if you don’t have it yourself then you know someone who has had to face that diagnosis. The Emperor of all Maladies really is a biography of cancer, and the crash course that I think we all could stand to go through for a better understanding of this disease.

New Job: The Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

After an incredibly crazy month of traveling, interviewing, and moving I have officially started my new full time job at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. I announced on Twitter a few weeks ago that I accepted a position with DFCI as a science writer for donor relations, but I realized I never really gave my blog readers any background on what I’ll be doing. After all my whining and pontificating about growing up and joining the work force, it wouldn’t be right to not explain what my new job is all about.

As a science writer for donor relations my role is to research, gather information, and interview PI’s about research projects (mostly pre-clinical and clinical) on specific beats that I’ve been assigned. The beats are all specific subdivisions regarding research at DFCI, it could be a specific group of cancers like women’s cancers, a particular research group or institute or a particular program or approach to looking for treatments. DFCI is one of the oldest and most accomplished cancer research institutes in the United States with a serious commitment to both research and patient care.